Balanced Information Briefing

This briefing is the product of a process of collaborative co-production and iterative improvement. The lead authors were Tereza Horejsova and Stephanie Borg Psaila from DiploFoundation (“Internet and me”), Anouk Ruhaak (“My data, your data, our data”), Chiara Ullstein and Michel Hohendanner (“from the public sphere to the digital public sphere”), Matthias C. Kettemann from the Leibniz Institute of Media Research (“Good news, bad news, fake news, real news”) and Chiara Ullstein (“Governing Artificial intelligence”).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Table of content

Editorial

Welcome on board

Internet?!

Wait, but why?

The information briefing

Internet and me

What is Internet?

The Internet has been around for over 50 years

A network of networks

How the Internet evolved

Who has access to it?

Who makes the Internet work?

Is the Internet good or bad? Identifying some of the main problems

My Data, your data, our data

We leave a trail online: data

From breadcrumbs to profiles

How data about you is used

It’s not all up to you

Why it is important now

There are different ways to see data

Data as a private resource that can be owned

Data as Labour

Data as our personal reflection

Data as toxic waste

Data as infrastructure

Who should benefit from (digital) data?

Towards a strong Digital Public Sphere

What is it and why is it important

A tremendous opportunity

From the “Public sphere” …

… to the “Digital public sphere”

How can we sort out the amount of information?

A healthy public sphere

Good news, bad news, fake news, real news

What is disinformation and why is it an issue?

Freedom of expression and its limits

Is disinformation a real problem?

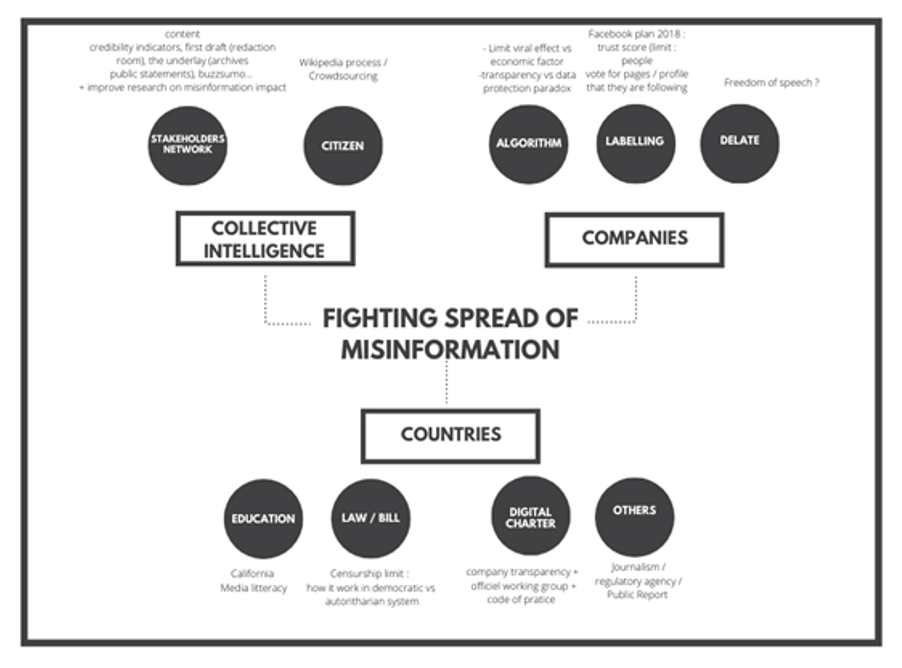

Tackling Disinformation

The role of states and governments

The role of platforms

Should the users be responsible?

What about civil society and the media?

So, which tools should we implement?

Governing Artificial intelligence

What is Artificial Intelligence and why it is important

Beyond the hype

Current Application Areas of AI

What is Machine Learning?

The Machine Learning Process

Some challenges of Machine Learning

Who is responsible?

Towards rules for governing AI

Looking forwards

Who should take care of the Internet?

What is “governance” and why it matters

Internet Governance 101

We the internet

Lexicon

Editorial

Welcome on board

How would you draw a picture of the Internet? You might draw a computer, or a mobile phone or tablet. Perhaps, you would imagine several computers connected to one another, illustrated by random interconnected lines. This is how the Internet looks like for most of us, the users. If you think about the technology behind the Internet, that image is correct. The Internet is a global network that connects computers and devices, and each of us who uses the Internet. It’s also everywhere: from our homes and offices (think also kitchen appliances and vehicles!), to open spaces, government offices, and public transport.

But to understand the full picture, we need to look beyond the network, and ask: what is this network able to do?

Internet?!

Who is behind it, and does anyone own the Internet? Do we need to worry about how the Internet is managed, and can we trust the system? Who will ensure that the Internet is not used to harm us? How does it benefit society the most? In what ways has it made our lives easier? Are our lives becoming less private with the Internet, or is it making life more private and anonymous? What about the impact of the Internet on the economy and employment? Will technology make our jobs redundant? Also, are we addicted to the Internet, or is this really the most useful tool for so many aspects of our everyday life? And what about our identity online? What will it allow us to do that I cannot do today, and how safe is it from criminals? What happens with the data we produce?

Wait, but why?

Let us take a step back.

Nearly 55% of the world’s population is now connected to the Internet. If the degrees of access and uses are different, the Internet represents a tremendous opportunity for humanity. Through the multiplication of networks, the possibility of being connected almost instantaneously to information and individuals, the Internet has revolutionized human relationships and society, to the point of being perceived as the space for the advent of a society of freedom and equality between all human beings. However, as humanity benefits from these advances, drawbacks become more visible. The security of Internet users, addiction, data protection and disinformation are all subjects on which political decisions must be taken that will steer the future of the Internet.

The Global Citizens’ Dialogue on the Future of the Internet aims at putting citizens in the loop of the decision on this future, your future. Our future. From high connected areas, to less connected ones, every human being is somehow impacted by what is happening on the net. This Dialogue engages thousands of ordinary citizens around the world and covers dozens of countries, in order to open a channel of communication between you and the decision makers. It is the largest ever citizen deliberation of history. And the first on the Internet at that scale. Congrats!

The reason why we invited you is because we want you to express your hopes, your fears, and your recommendations on the future you want for the Internet. We will bring the results of this discussion to the decision makers and provide them with first class materials to support their discussions and decisions. They will see the power of including you in the discussion.

You are invited to join the global conversation.

We are about to embark on a journey which will take us to the core of our digital past, back to the present, and into the future. We will start by discussing what is the Internet for you and how the COVID19 outbreak has impacted your relation to it. We will then focus on the question of what is a good digital identity. More particularly we will discuss the question of how to handle our data. We will then move to the discussion around the modern challenge of information and discussion on the Internet and whether we can or should trust it. The next topic that will get our attention is the so-called “Artificial Intelligence” and its management. Finally we will address long term questions and talk about how we take decisions on the future of the Internet.

The information briefing

The text you have in your hands or on your screen is there to guide you through the very complex jungle of the topic you are going to discuss. They will help you understand the concepts and the discussions. They do not aim at being exhaustive, they aim at giving you the toolbox to understand the major discussions happening nowadays and in the coming years.

If they are too long for you, don’t worry, you will have a summary during the deliberation day and the facilitator in your group will also have read them.

Welcome on board and thank you for being there!

What is Internet?

The Internet is a global network that connects computers and devices, and each of us who use the Internet. It’s also everywhere: from our homes and offices (think also kitchen appliances and vehicles!), to open spaces, government offices, and public transport.

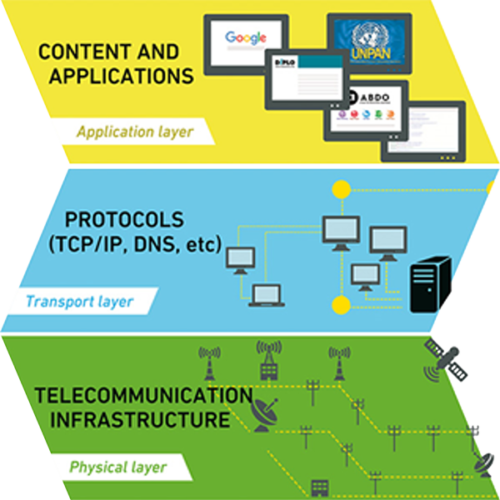

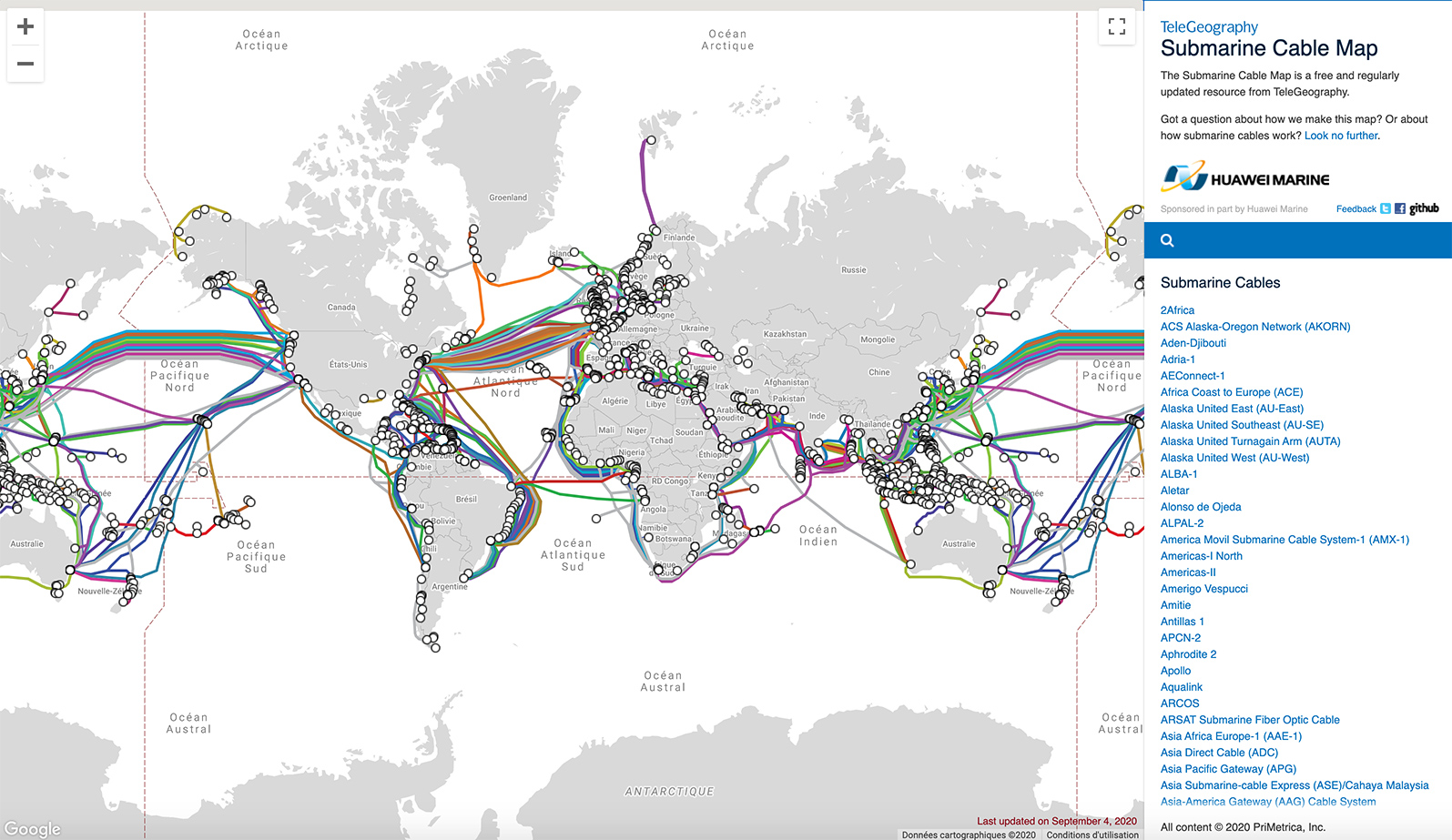

Internet basically runs on three levels as the following image displays:

- The telecommunications infrastructure (bottom) or the physical layer through which Internet traffic flows (cables and lines, modems and routers);

- Internet protocols (IP) (middle) or the transport layer, including the domain name system (DNS – the address book), the root zone, and technical and web standards (software that make internet works), which allow the information to find its way.

- Content and applications (top) or the application layer. These are for example the websites and services you use on the Internet, your social media or video platform, etc.

The Internet has been around for over 50 years

The Internet was invented by scientists who wanted to link their computers to one another. Scientists soon began to discover the broader potential of this early project, and found a way for computers to share information, similar to what the telegraph or phone system did in the years before. The original idea was for this network to establish a secure and resilient military communications network. Over time, the ‘decentralized’ nature of the network became obvious: if one part of the network breaks down, the rest can still continue to function.

A network of networks

So how was the network built? Linking the computers was relatively easy: Cables would do the job. Connecting a computer in one continent to another computer in another continent, with an ocean in between, was also straightforward. Cables were installed underwater at the deepest level, which is by the way the system we still use today.

For information to pass through the cables, scientists had to invent a computer language that would break the information into small pieces, send it across cables, and assemble it back once it reaches its destination.

How do the small pieces know where to go? Scientists also invented an address book for the Internet, which made it easy for us to direct the information to a specific e-mail address, or to request our browsers to take us to a specific website.

How the Internet evolved

Thanks to the network, the language, and the address book, we are today able to use social media, communicate through e-mails and other platforms, look for information, listen to music, watch videos, purchase goods and services… The Internet has changed and improved the work of major industries, such as manufacturing, healthcare, and transportation, as well as the public administration and governments.

What is the difference between the Internet and the World Wide Web?

The terms Internet and World Wide Web (www) are sometimes used interchangeably. In reality, they mean different things. The Internet is the infrastructure which connects everything together; the www is just one of many Internet applications that we use to communicate, access websites, etc. Think of the postal system: the Internet is similar to the network of post offices and letter boxes, while the www is similar to the letters and parcels we send via the system. At the same time, the www is probably the application that made Internet use grow exponentially.

Who has access to it?

Half of the world’s population takes the Internet for granted. Yet, the other half still does not have access to the Internet, and therefore, cannot reap the same benefits. In a number of developing countries, the basic infrastructure – such as electricity – is simply not there. Since countries’ resources may be extremely limited, governments may be more inclined to spend the little available resources to fixing issues such as food scarcity, or poverty. In several countries where an Internet connection is available, the cost of the service may be incredibly steep (sometimes costing a month’s salary or more). As investments to build the infrastructure in these regions are high and the legal framework may be complicated, companies are not inclined to lower the costs of access and governments may not be in a position to invest the needed sums.

While affordability is the main challenge, it may be surprising to learn that some people are unable to find content in the language that they understand (50 % is in English and only 2% in Chinese). And while some may understand one or more of the most common languages used on the Internet, disadvantaged groups may find it too difficult to learn how to use the Internet.

Who makes the Internet work?

- Governments create, or adapt rules, to allow e-commerce to grow, to provide the private sector with enough incentives to invest, and to regulate other areas of the Internet. Some governments use the Internet to launch cyberattacks, or to suppress those who complain about their governments’ behaviour.

- Civil society speaks on behalf of the users, and so, civil society organisations alert governments and companies of any wrong-doing that we may be suffering from, or raise the alarm when user rights need to be protected. Some organisations are more active than others.

- Through research, academics and their institutions contribute by looking at issues beyond the commercial aspects. They reflect on the theory behind how everything works, and in many cases, apply this to real scenarios.

- The technical community and the private sector push the boundaries of what technology can do for us today and tomorrow, and in the next 5, 15, or 50 years (think artificial intelligence or virtual reality). Sometimes, the rush to launch new products gets so intense, that other aspects, such as the possibility of products being hacked, is not tested enough (and that’s why we are often asked by the occasional pop-up window to install a security update, or a patch…).

Each of the involved parties, also called stakeholders has a role to play; each stakeholder also has an interest in furthering specific aims, which adds to the complexity.

Is the Internet good or bad? Identifying some of the main problems

In the offline world, many of the things we use in our everyday life can be used by wrong-doers. For instance, we normally use money to buy goods and services. But money can be used to exploit others or can get stolen. Similarly, a computer can be used by children to learn new things, but could also be used by criminals to make inappropriate contact with children (not every risk manifests itself, in reality). Social media is generally used for communicating with family and friends, but can also be used to spread hate and harass others.

In the framework of the Global Citizens’ Dialogue on the future of the Internet we want to focus on following topics, which are at the center of the decision making process and will highly benefit from the articulated voices of citizens of the world, of your views. These issues are:

“My data, your Data, our data”. This will bring us to tackle the following question: “What should happen to the data produced by us and others?”

Ensuring a strong Digital Public sphere. The core question here is: “How to fight against the spread of false information online and their consequences?”

Exploring and governing Artificial Intelligence. The core question here will be to understand your hopes and fears concerning AI and the priorities you see at international level.

My Data, your data, our data

We leave a trail online: data

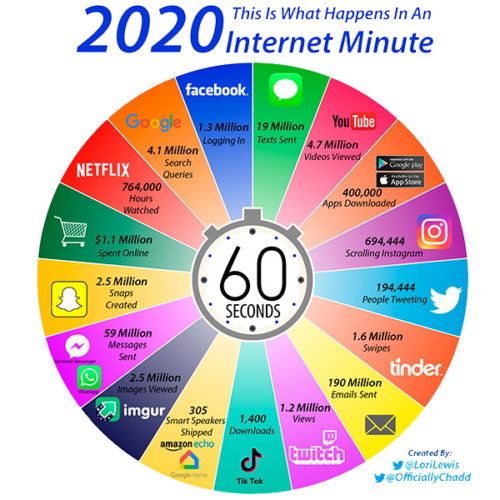

Every time we open a web browser, perform a search query, log into a social media platform or even check the weather online, we leave a trail of digital breadcrumbs. Websites trackers and cookies that allow them to track how much time you spend on a page, how long it takes you to read an article, what videos you watch etc. Every day about 2.5 quintillion bytes of data is created and stored. That’s the equivalent of about an hour worth of high-resolution video, for every person on the planet, created every day.

Web trackers

Web trackers are pieces of code that record your online preferences. One famous example of a web tracker are “internet cookies”: tiny data containers that allow websites to save data about you on your device. The next time you visit that site, instead of getting to know you all over again, it will remember certain characteristics about you. Other trackers take the form of scripts that are hidden on websites – sometimes in a single pixel – and run in the background, recording things like your IP address. Some trackers follow you from one website to another and keep track of your clicks and other activities as you go.

Now that our (household) devices are connected to the internet as well, that number is only slated to grow. Our smartwatches track our steps and heart rate and send that data back to the company that produced it; Our voice assistants are actively listening for our commands, recording and storing what we tell them; Smart energy meters track and store energy consumption; Our phones may be silently recording our locations and send that data to various app developers and phone producers.

Data collection is nothing new. For centuries, humans have recorded their stories on cave walls, engraved them in stones, or documented them on paper. What makes digital data collection different is that it’s become trivial to store large amounts of data for long periods of time and link existing data to new data sources. Consequently, the location data you share with your maps app today, could be used to obtain insights into routines, years from now. And as more of our lives have moved online, it’s become possible to not just record and store our writings and communications, but to also collect data about how often we communicate, how many times we open a certain website, or search for a specific term. This data about data is called meta-data.

From breadcrumbs to profiles

On its own, each digital breadcrumb reveals very little about you, but when put together they can be used to create extensive profiles of you: who you are, who you relate to, your preferences, your interests, your habits, the habits of your loved ones and how you engage with the various digital services you use every day. Think of these as virtual representations of yourself.

How do those profiles come about? In some cases the digital platforms you use to communicate with your friends, may be able to accumulate so much information about you that they can create extensive profiles of you, without any external data source. They will use what you give them in the form of posts, messages, likes and and reposts. In other cases, so-called data brokers hoover up the trails of digital breadcrumbs you leave online and combine this with public data sources and information they buy off other data accumulators such as credit card companies.

For the moment, we have little control over the profiles that are created about us. We often don’t know who is creating those profiles, whether they are accurate (they are often not) and we have few ways to rectify errors they may contain. This is especially problematic when these sources of information form the basis for decisions of whether or not we should be able to access specific services (loans, housing etc).

How data about you is used

Advertising

The most common use for such profiles is advertising. Ever received an online ad for shoes, moments after you searched for a new pair of boots online? That’s not an accident. The trail of data you leave online is used to uncover what ads you are most likely to click on, or which products you are most likely to purchase.

Attention

Social media platforms want you to stay engaged and will use data about you to understand how to keep you hooked to their service. Based on what you have liked or posted previously, they will serve you content that is most aligned with your interests. Some of this content will be paid for by advertisers, such that the platform receives a payment every time you click on it. This is one of the reasons why so many platforms are able to offer their services for free to you, the user.

Improving digital products

Data is also used by digital service providers (the people building the apps you use) understand your preferences and make their services better to better serve your needs. For instance, if you click a button and then close the website, they may conclude the button is not working properly and fix it.

Coordination

During this COVID-19 pandemic, governments started collecting data about infection rates and COVID-19 hot spots. While much can be said about the effectiveness of such data collection, the general sense is that knowing what is going on on the ground can help coordinate responses. This is also true in other crises. For instance, shortly after an earthquake, information about population density, or who was at home when the earthquake occurred, allows disaster response agencies to efficiently allocate available resources.

(Automated) decision-making

Digital data is increasingly used to automatically make decisions. Algorithms can be trained on eye scan data to learn how to diagnose specific eye diseases; Facial recognition is widely used in airports to automatically assess who you are; Insurance providers use data about your income level, your friends, or the neighborhood you live in to calculate your premium; Loan providers use similar data to assess your credit risk.

Whether these decisions are fair and accurate largely depends on whether the data used is both accurate and complete. For instance, facial recognition systems trained on white faces have trouble recognising the faces of People of Color. Or, someone with an excellent credit history may still receive a bad credit rating when they live in a relatively poor neighborhood. More on that in the part on Artificial Intelligence below.

Threat assessment

Security agencies use large amounts of personal and aggregated data to determine whether individuals represent a threat to national security. In 2013, data leaked by Edward Snowden revealed that the US National Security Agency had collected troves of data on people living in and outside of the US. The NSA says that it needs this data to keep the country safe. Privacy advocates on the other hand hold that this amount of data collection is invasive and violates citizen’s right to privacy.

Control behaviour

Digital data helps companies and governments monitor the behaviours of users and citizens alike. Such monitoring can be used to encourage certain sets of behaviours (e.g. stopping for a red light), while preventing others (e.g. posting nude pictures on social media, or committing a crime). Sometimes, control takes the form of a gentle nudge, other times it takes the form of social credit scores. A scenario in which every citizen receives points for behaviors that are deemed socially beneficial, while receiving negative points when engaging in socially unacceptable behaviors. Such point systems can then be used to grant individuals access to services such as housing, public transport, or credit.

Accountability

Sometimes we need data to be able to hold people accountable. For instance, information about public spending allows us, the general public, to detect corruption early on.

Making sense of ourselves

Researchers, journalists and other thinkers rely on digital data to help us make sense of the world, people, nature, society, our history and so on. This research, in turn, helps us cure diseases, define policies, or create novel solutions for urgent problems.

It’s not all up to you

It’s tempting to think of the data we share online as only about us, and as the decision to share things about ourselves as conscious decisions. But that’s often not true.

A lot of data is shared. Take DNA data for example. You may decide to share your DNA with an analyst to understand more about your genetic make-up. In that case, you are also revealing data about your (unborn) family members who share your DNA. And it’s not just genetic data that is shared. Messages you send to friends, images that include multiple people and stories you created as a group all represent instances of shared data.

But even when data is really just about you, it can still be used to reveal information about others as well. If one twenty-something-year-old student shares information about their music preferences online, this data can be used to infer the music preferences of other twenty-something-year-old students. Or, data about your income may be used to make inference about the general income level in the neighborhood you live in.

Even the decision not to share data can end up affecting you: imagine what would happen when all the healthy people decide to voluntarily share data about their daily exercise patterns with health insurance companies. They might receive some benefits in return for this data. You, a not so healthy person, decide not to share similar data out of fear your health insurance provider will hold this against you. However, by not sharing such data your health insurance provider may already be able to infer that you carry larger health risks and increase your premium.

Sometimes you don’t even get a chance to decide whether or not to share data about yourself. There are many instances where data about you is collected without your knowledge. Street cameras might record you without you being aware and most meta-data is collected silently, in the background. How do we make decisions about this type of data collection?

Why it is important now

The troves of digital data that we collect about ourselves and our environments could potentially serve humanity and enhance our lives. Data about our online behaviours can help scientists predict ; Our driving data helps engineers build self-driving cars that are less prone to cause accidents; Data about our health could allow for new, automated, diagnostic tools. But as we have seen, collecting and using digital data can also cause harm to both individuals and society at large. That’s why it’s important for us all to have a say in what we want to collect, how we want that data to be used and for what purpose. And we need to have that conversation right now.

Why? We reached a point where our ability to participate in society depends on our use of digital tools. Public policy announcements are increasingly made on social media platforms, business meetings have moved to Zoom and signing up for events often requires a Facebook account. These tools provide a lot of convenience and help us connect to one and other even when pandemics keep us locked in our houses. Yet, our reliance on these tools for our daily functioning also makes it harder to make real choices about what data about ourselves we want to share with whom. In other words, the decision between sharing data with a social media platform or losing access to your friends, may not be a real decision at all.

At the same time, our governments, banks and digital services are increasingly relying on the data we share online to make decisions about us: Decisions about where we live, what resources we have access to and whether or not we are eligible for government support. As a result, for better or worse, what we reveal about ourselves today can have a significant impact on our lives tomorrow.

The question then is how we make decisions about this data. How do we capture the social and economic value of the data we generate, while simultaneously reducing the harms it may produce? Who should be in charge of deciding what data is collected and used? Should it be each of us individually? Do we want our governments to decide for us? Or, should it be left in the hands of the organizations collecting the data?

Relatedly, who should benefit from all this data? Should it be the companies who collect it and provide us with free services? Or should all this data first and foremost benefit the public good? Do we want to distribute the benefits of data equally? Or do we think it is fair for some to receive a larger share of the pie?

There are different ways to see data

1. Data as a private resource that can be owned

You may have heard people say that data is the new oil, a resource that will power the next wave of innovation. Except while oil is extracted from the natural world, data is extracted from human beings and the environment. This begs the question of who should own this resource. Is it the person extracting it? Or the person from whom it is extracted?

In the first case, data would be owned by the corporations and other entities that collect digital data. These are the search engines, the social media platforms and voice assistants. They are the ones who put in the money and time to build the platforms and often offer their services for free. Why not allow them to own the data they collect? And if they would have to give this data away, would they still offer these services for free?

In the second case, data would be owned by those it is about. These are the users of the platforms and the search engines. If companies are to make money off of data about you, should you not enjoy a share of the profit?

In both views, the owners of data should be free to decide who gets access to their data and should be able to sell their data for a profit. Once the data is sold, the old owner loses the right to make decisions about it and the new owner gets to make those decisions. Much the same way we buy and sell books, bicycles, or houses.

Things become a bit more complicated once we consider that data is often ‘extracted’ from more than one person, or from a process. Who owns the data in those cases?

2. Data as Labour

This is a variation of the ‘data as a resource’ model and argues that the creation of data is laborious: When you post things online, share images or tag yourself in a post, you are essentially performing a little job (the creation of data) for which you should be compensated.

This view zooms in on the right to compensation for data and makes that data available for anyone who helps create it. However, it says little about how this relates to a right to control data about you, even if it is created by someone else. For instance, when one person creates data by writing a story about another person, should the latter also be compensated?

3. Data as infrastructure

Wikipedia defines infrastructure as “the set of fundamental structures and facilities serving a country, city, or other area, including the facilities necessary for its economy to function.” These include highways, railroads, internet cables and telephone lines. Given the increasing importance of digital data for the functioning of society today, it is not hard to see how we might consider it as part of our core infrastructure.

From such a perspective, instead of leaving it to the individual to decide how they want data about them to be collected and used, we may instead look at larger communities, or governments to collectively determine how to best make this data available to the public good (as a core piece of infrastructure). Of course, just as individual and communal needs should be taken into account when building a road, an individual’s right to privacy, as well as the negative externalities of data collection and use should be taken into account when making public decisions about data. However, in this scenario, the ultimate decision would lie with, for instance elected officials, or the communities and networks that rely on data for their society or economy to function.

One complication with this view is that it leaves vague who should decide: should it be small groups of people (e.g. your family) making decisions together? Or your national government? And would the answers to these questions change depending on the type of data or the use case?

4. Data as toxic waste

While there are many good reasons to collect and use digital data, some argue that the bad outweighs the good. They liken the collection of data to the accumulation of nuclear waste. Just as nuclear power holds a lot of promises, it’s by product, toxic waste, is hard to discard and has a long life span. The same can be said for data. While data can be used for research that benefits the public good, it’s by-product in the form of surveillance and control is deemed dangerous (and permanent).

In addition to the surveillance risk, data collection and storage also has an impact on the natural environment. Some experts have estimated that by 2025, the communications industry will account for 20% of all energy consumption. Data storage and sharing of data between services is a big part of that number. As a result, one argument against the storage and use of data is that we do not have the planetary resources to accommodate it.

When looking at data from this perspective, a logical next step is to curtail the creation of data; To only collect what is strictly necessary and discard everything else.

5. Data as our personal reflection

Instead of viewing data as a resource to be exploited, we could view it as a reflection of the thing it is about. You are reflected in data about you, your relationships are reflected in the messages you write, your behavioural patterns are reflected in the way you drive your car through a city. Data is like a reflection in a mirror.

When considering data in this way it becomes more natural to ask who should control this reflection. Data rights advocates argue that everyone should have the right to decide what they want to reveal about themselves in any given context. Moreover, you should never be able to sell these rights by selling your data. This is where the data rights view differs from the ‘new oil’ perspective: while resources can be bought and sold, fundamental rights are inalienable. That means you can never sell them off, no matter how much money you are offered. Just like you should never be able to sell your mirror image, or your shadow.

Here too, things become a bit more complicated once we consider that data is often a reflection of more than one person, or a reflection of a process. Who holds the rights to decide about data collection, access and use in those cases?

Who should benefit from (digital) data?

If data is so precious, important, sensible … Who should benefit from it? There are many options on the table:

- The person the data is about: if data about me is used, it should benefit me and should be used in a way that benefits me – even when that comes at the expense of someone else. This option assumes the data is always about someone.

- Communities: if data about me is used, it should benefit my community and should be used in a way that benefits my community (even when that reduces benefits to me) and minimize the harms to that community and its members. This assumes we can define a community.

- Society at large: all data should only be collected and used for purposes that benefit society at large and minimize the harms to society and its members. This assumes society is relatively homogenous.

- The entity collecting and using the data: At the moment corporations have the most data. In this option corporations should collect and use data as they see fit. They are the ones investing in new technologies and deserve to use the data they collect. In this option the data is in private hands. Sometimes the ta collecting entity is a public entity.

- No one: we should not be collecting online data in the first place.

And you?

Towards a strong Digital Public Sphere

What is it and why is it important

A tremendous opportunity

Never before in the history of humankind have we had access to so much information. And the way we access this information has changed tremendously. The number of videos, books and stories we can see, read and listen to has exploded. We select what, when and on which device we see and read news and learn new information about the world and others in it.

We interact with other citizens, with our government, with companies and all kinds of organizations directly and with almost no filter. This has not always been the case.

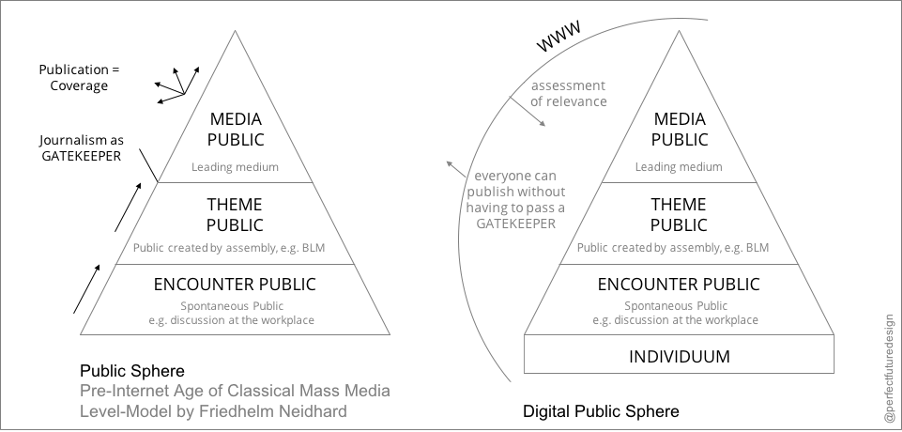

From the “Public sphere”…

When we talk with our family and friends, when we talk with colleagues and peers, we become part of what can be called the “public”. We interact with another and give and build our opinion and views on matters important to us and the community. But we are not the only one doing that. Journalists and governments, companies and associations are also participating in that discussion on the common future and on topics important for society. Or funny, or entertaining. This is what we can call the “public sphere”. It is a concept that has been debated over many centuries and which meaning has profoundly shifted over time.

Traditionally and during a long period of time the public sphere was defined as “the age of the mass media”. This was referring to the fact that newspapers, radio and the TV were the main channels of this public discussion on the common future. To illustrate this situation we can think of a pyramid:

- At the bottom we find “you and me”, citizens discussing in their family, at the workplace, etc. In this space everyone is both “sending” messages (let’s call that a performer) and “receiving” messages (let’s call that an “audience”). We call that performance and an audience role.

- In the middle we find individuals, groups and/or organizations that come together around specific themes, e.g. environment or internet for example. These groups are more inclined to send messages. They are mostly “performers”.

- At the top of the pyramid, we find “the media” who produce and distribute information and messages. They are performers.

So if you wanted to discuss something largely in society, the only way was to go through the media level. And journalists played a role of filter.

… to the “Digital public sphere”

The spread of the internet changed this situation completely: The internet allows every individual to publish contents. So everyone one is at the same time the audience and the performer.

This is very interesting as it breaks the traditional pyramid of information exchange and opens a very vibrant and lively public sphere. We are able to communicate directly with our peer citizens, not only locally but globally. Interesting, important, funny information can spread with almost no cost all over the world.

For example during the COVID crisis, health agencies could deliver up-to-date data and information about the outbreak everyday, which was relayed on social media platforms so that billions of users could see them quickly.

This also leads to a core challenge that is the one of the quality of information: How to make sure that what we read and see online is true? How do we ensure that no one is harmed when being online?

Because if what we see and read online is not of quality, if we can be attacked online, then the digital public sphere ceases to be a place for the good of Humanity and it becomes a toxic place. A dangerous place.

Let’s dive into the main arguments, questions and controversies.

How can we sort out the amount of information?

The first big question is to understand which topics from the huge amount of information on the Internet are interesting for the community at large and should be shared more? On the contrary which are uninteressant or even harmful and should be shared less or not at all?

Nowadays, the main tool that helps answer that question is called an algorithm. An algorithm is a piece of software (a computer program) that sorts data automatically, without human action. It is written by humans of course. But it sorts data on its own.

So in the digital public Sphere, the connection between the producer and receiver of a message is done by a computer program. And a huge part of this connection is made through so called social media platforms and through search engines.

This poses again the question of the “gatekeeper”. In the mass media era journalists were the gatekeeper. In the digital era, the gatekeepers are the algorithms and the company that develops them. This has brought a lot of people to criticize the power of technology companies and social media companies.

For a long time, those companies have considered that it was not their role to fact-check the content put on their platform as this content was produced by the users and their freedom of expression should be safeguarded. And it is true. Users are responsible for what they look and like and for what they publish.

At the same time recent scandals linked to national election processes or the existence of harmful and racist content on the Internet have pushed companies like Google, Facebook or Twitter to take action and to affirm their social responsibility and start monitoring the content put on their platform for harmful content.

Some states and international organizations have also started to regulate the digital space.

A healthy public sphere

The Internet is here to stay. So it is very important to define the boundaries and rules we want to give for this new digital public sphere. We are at a moment in time in which rules are being shaped and discussed, tested and improved. This is why we need your input.

What do you think? What is for you the difference between public and private? Is there a clear limitation? And is there a difference between the “analog” and the “online” dimensions? Based on your experience as citizens, what should a healthy digital public sphere look like?

Good news, bad news, fake news, real news

What is disinformation and why is it an issue?

One very big question when discussing the digital Public sphere is what we often call “Fake news” or to be more precise “disinformation”. These are pieces of information that are based on or communicate empirically wrong information with the goal of misguiding readers. But not all disinformation is false. Some disinformation contains only or mostly correct information, but the information is used selectively in an attempt to shift the frame of reference of the debate and influence the political narrative selectively. This is called misinformation.

Disinformation is a very old phenomenon. For example as early as 1275, the King Edward I of England edited a “seditious speech act” prohibiting anyone from “cit[ing] or publish[ing] any false news or tales whereby discord or occasion of discord may grow between the king and his people.”

The problem is that humans are especially bad at recognizing false from real news in the absence of verbal cues. Without context, we are lost and tend to believe anything.

Human biases and cognitive deficiencies make us susceptible to content that plays to our fears and seems to convince us that we were right all along (“See, I knew that the government was hiding something …”, “See, I knew that rich people can bend the rules …”.)

To make things worse and as we have seen before, the key difference today is that we are in a digital public sphere. Disinformation:

- Can easily be shared (it can even go viral, that is: be shared exponentially, quickly and widely).

- Is instantaneous; The moment you click “send”, it is online everywhere.

- Is cheap: large parts of the population can be reached at minimal costs to the purveyor of disinformation.

- the anonymity and lack of face-to-face interaction reduces the willingness to engage in cooperative behavior and increases aggressive behavior and speech.

Freedom of expression and its limits

Freedom of expression, which is guaranteed both in national constitutions and in all universal and regional human rights treaties, constitutes one of the essential foundations of society and one of the basic conditions for progress and for each individual’s self-fulfillment. It is important to note that not only information or ideas are protected that everyone agrees with, that are favourably received or considered inoffensive, but also ideas that may offend, shock or disturb. Sometimes these even need special protection. Ideas change over time and ensuring that new ideas can flourish can be beneficial for all.

Freedom of expression by itself is a key enabling right: offline just as online, since, for many people, the Internet has become one of the principal means by which they receive and impart information and ideas. User-generated activity allows for an unprecedented exchange of ideas, instantaneously and (often) inexpensively, and regardless of frontiers.

Truth should reign free. But it needs some help. As the global public had to learn, online social media services were used by bad actors to spread disinformation. From the US to Brazil, from Indonesia and Mexico to Kenya, disinformation brokers (some who have been identified, some who remain anonymous) have tried to sway the public opinion and to attack critics.

Yes, ideas should ideally fend for themselves. Bad ideas that do not move the world in the right direction should ideally just fall out of favour. But in times of strategic disinformation campaigns, the disillusionment of parts of the populace with traditional ideas about politics, the growing influence of masterful manipulators in politics, and the rise of nationalist movements across the world, this is not enough. The truth needs help, especially as strategic lies are often connected to (or lead to) human rights violations, often on a massive scale.

Is disinformation a real problem?

Studies on disinformation come to diverging results. On the one hand, the concrete impact of disinformation is hard to pinpoint, though not non-existent. On the other hand, disinformation actors seem to take up a disproportionate part of the news about online media practices. This reinforces the impression that the Internet can be used as an effective forum for disinformation. Others argue that the main threat of disinformation is making everyone argue more and trust each other (and reliable sources of news) less.

On the one hand, trust in traditional institutions – doctors, newspapers – slowly declines and people start searching for alternative news and opinions online. On the other hand, the diversity of news and opinions online makes it easy for readers to ‘escape’ from news that do not fit their opinion and search for news that makes them feel safe and understood by reaffirming their own biases (even and especially when they hold fringe or minority views).

Tackling Disinformation

The role of states and governments

States have the primary responsibility and ultimate obligation to protect human rights and fundamental freedoms, including in the digital environment. Coupled with the obligation to respect their commitments under international human rights law, they must introduce regulatory frameworks, including self- or co-regulatory approaches, which allow for differentiated treatment of expressions online, including effective and appropriate remedies. But it is thus not enough for states not to interfere with freedom of expression, states also have a positive obligation to protect human rights and to create a safe and enabling environment which allows all persons to “participate in public debate and to express opinions and ideas without fear, including those that offend, shock or disturb state officials or any sector of the population“ (CoE).

States are, of course, not the only actors in ensuring human rights online. Internet intermediaries, too, have duties under international and national law.

Internet users engage disproportionately with sensationalist content. Players on the disinformation market use human biases and cognitive deficiencies to bait online users into consuming disinformation. Does this mean that states should outlaw disinformation and criminalize purveyors of disinformation?

Some disinformation is already illegal but not a big part of it. If new rules limiting the right to spread untruths are considered necessary, the limits on restrictions to freedom of expression needs to be considered.

In this case the role of the platforms that are distributing the information becomes particularly important, also when state actors refuse to enforce human rights online or activate laws designed to address disinformation and suppress dissent.

The role of platforms

So: Should companies (be allowed) to continue to carry disinformation, even if it is widely shared and drives traffic to their sites and can thus be monetized? Or is it better – and more responsible – to quickly delete content that is untrue or detrimental for social cohesion and to clearly take a step again coordinated inauthentic behaviour, as big social media companies have successfully started to do?

People can use their own opinion to judge the truthfulness of content. If content is deleted, the impression may emerge that a platform is politically biased. While platforms can delete content under their terms of service, there is often a tension between these and national laws that has to be solved. Some content is illegal in certain countries, and legal in others. It is very difficult to prove that a certain piece of content is wrong and even if it is correct, it may be societally dangerous if it shifts the frame of reference that contains only highly selective “truths”.

But is it a good idea to have platforms assess the correctness of content and the reliability of its authors and mark content as such? Does this lead to more trust – or do users feel disenfranchised and even less trustful of the platform? Deleting problematic content is not the best solution.

Why not cooperate with fact-checkers and provide notices to content which may be problematic? Then readers can immediately see if a piece of news is actually fake, and what level of trust the author of a post or video deserves. Users can be invited to contribute to this fact-checking exercise. Social media companies can then use algorithms to downgrade misinformation and to disincentivize sharing. If users choose to share a problematic piece of content, they are immediately put on notice. Links can lead users to a correction, such as a trusted study on the subject or an article from an established news organization.

Should the users be responsible?

Another solution is to give users the responsibility. At the end, any citizen should be responsible for what they share and see online. So why not focus on educating citizens to tell when a piece of news may be disinformation. If citizens have the possibility to easily report doubtful content, maybe they will take action and through collective intelligence, Disinformation will go down in the rating of algorithms.

Further than a technical possibility, citizens could be supported by programmes of education to “digital literacy” that would allow them to better judge and navigate the information they see online and to better judge the content they publish themselves.

What about civil society and the media?

Another approach is to rest on the network of stakeholders that work in the domain of information. So maybe journalists should help in sorting out the flow of information. That would make them again gatekeepers. But maybe it would make them the best defense against Disinformation too. Journalists have started such initiatives all around the world and build fact-checking platforms.

Governing Artificial intelligence

What is Artificial Intelligence and why it is important

Beyond the hype

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are two words that are used a lot these days. These technologies are depicted either as the solution that will save the world or as the last step before apocalypse. But to be true, there is a real discussion about what these technologies actually are, and what they really can do or will be able to do in the future.

Many have tried to define the term AI, however, there is yet no definition that everyone agrees to. Often, definitions are very vague, making it hard to grasp what AI is actually about. For example, in an often quoted general definition, AI is described as “a technique that enables computational systems to mimic any type of intelligence”. Simplified, this means that a machine is capable of solving specific problems. While there are many mystic and science fictional ideas on AI out there, today, only very well defined problems can be solved by AI systems. This field is often referred to as narrow AI. In comparison to narrow AI, general AI refers to systems that can perform any intelligent task that a human would be able to perform.

Because general AI is still more science fiction than reality and very hypothetical, we will stick to applications of narrow AI that can actually be found out there. Why is it so hard to find a definition that is broadly accepted? The reason is that up until now, not even human intelligence has been properly defined. Not to talk about animal intelligence. Think about it. What do you consider as really intelligent? Besides the issue of intelligence itself, there’s also disagreement on what AI comprises. While some refer to AI as a technical approach, others define it as the combination of software, hardware and data. In any case, AI comprises various tools and methods.

Current Application Areas of AI

Let’s briefly look into a few application areas that you might be familiar with.

- Speech recognition: Siri by Apple and Alexa by Amazon include both intelligent systems. These systems use AI to recognize speech inputs.

- Personalization: Several online services like social media platforms or Netflix and Amazon use AI to personalise the content presented on the webpages. Online services learn from your and other user’s previous behavior, e.g. watching only thrillers or buying primarily science fiction novels. Accordingly, content that most likely fits your interest is recommended to you.

- Email filtering: Email services use AI to distinguish between for example spam and relevant emails. Some service providers even filter out incoming emails that they consider advertising or social media into respective email folders.

- Applicant screening: Some companies receiving a lot of employee applications use AI to filter suitable applications from less suitable applications. The AI helps to make a preselection of incoming applications.

- Clinical diagnosis: In medicine, AI is more and more used to support the work of doctors in their diagnosis.

Of course, there are many more application areas. Some of them have an incredibly positive impact on individuals and society as a whole and bring great opportunities. In other applications, however, it turns out that AI discriminates and disadvantages certain groups of people. We will now take a look at why such applications can lead to issues of accountability, bias, transparency, data quality or other ethical problems. To do so, we will first focus on ML, to which AI owes its boom in recent years.

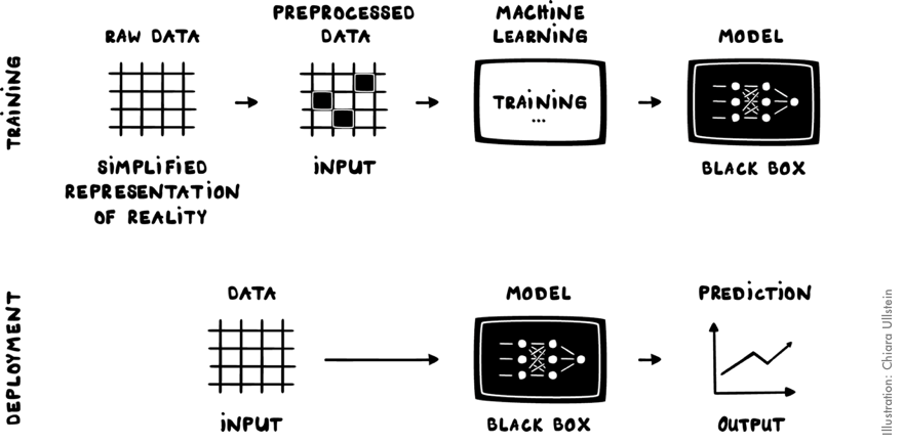

What is Machine Learning?

As a particular type of AI, ML is a lot easier to define. ML refers to algorithms and techniques that learn by themselves when confronted with data, observations and interactions with the surrounding world. First things first.

Algorithms are instructions to solve a task. Programmers write algorithms to tell a computer how to go about a problem. These algorithms essentially construct the digital world. Given rules and instructions, algorithms organize data and provide us with services and information.

ML algorithms are a particular type of algorithm. Instead of being programmed by human programmers, ML algorithms learn by themselves by a statistical approach. This means that ML algorithms are able to adjust initial parameters in response to their inputs and develop their own rules, by constructing a statistical representation of the environment given to them. These algorithms do not contain step-by-step rules, rather instructions on how to “learn” and on how to override which parameters. This process of learning is often also called training an ML algorithm. What ML algorithms are particularly good at is identifying patterns in very large data sets, due to their statistical approach. This characteristic enables us to use computers for new tasks that otherwise would have been too complicated or even impossible to code manually. Within the last decade, the advances in ML have led to great improvements in application areas where problems are solved through finding patterns in very big data sets, such as in the use cases mentioned above or in translation, image recognition and many more as well.

While all ML can be considered as AI, this statement is not true vice versa. For example, a regular calculator for school is a lot faster in calculating certain equations than an average human being. Therefore, it can be considered an application of AI. However, this school calculator relies on fixed rules set by humans and can’t learn by itself: They are not machine learning systems.

The Machine Learning Process

Thanks to the network, the language, and the address book, we are today able to use social media, communicate through e-mails and other platforms, look for information, listen to music, watch videos, purchase goods and services… The Internet has changed and improved the work of major industries, such as manufacturing, healthcare, and transportation, as well as the public administration and governments.

So how does machine learning work? And what does it actually mean to train an algorithm? Don’t worry, it will not get technical. In the figure below, you can see a simplified ML process with steps from collecting data to applying the trained algorithm in a specific context. While there are several ML methods, we will go through one exemplary method in order to introduce some processes usually involved. In general, the ML process of the exemplary method chosen can be split up in two phases:

- First, the ML algorithm has to be trained. The result of this training process is the ML model.

- Second, the model is then deployed in the desired area of application. The result of this step is a prediction, for example a probability of a patient to have a cancer tumor or the probability of a job applicant being a good match for the company.

Let’s look at these two simplified phases in more detail.

In the first step of this simplified training phase, data is collected. The data can be collected by people using several methods, for example by conducting questionnaires or taking pictures, or also automatically (collected or generated) by computers.

In the second step, the collected data is processed if needed. If so, in this part of the process relevant data is separated from irrelevant data. This step is often also called pre-processing. Pre-processing can also mean that data is augmented, in order to have cleaner and more precise data. The result of this step is a nice set of training data.

This training data is then used as an input for the actual training process. During this process a learning algorithm “learns” from the inputted training data. Learning here refers to identifying patterns in the input data by a statistical approach and generating a new set of rules based on the patterns found.

Essentially, a new algorithm is created. This new algorithm is the result of the training process and is called ML model. A ML model is often referred to as a black box, because depending on the chosen learning algorithm it is actually really complicated to understand what is going on inside the algorithm.

Before we move on to the deployment of this ML model, one more remark: If you train one learning algorithm separately with three different sets of data as input, you will receive three distinct ML models. This means that a type of learning algorithm can be used for generating ML models for very different application areas, for example language translation and stock market prediction.

After the model has been trained, it can be deployed. For this deployment phase, new data is taken as input. Then the magic of prediction happens: The model that you have trained makes a prediction about the new application area. Here, it is important to remember that any prediction will always be based on the patterns found in the training data during the training.

Sometimes this entire ML process is conducted by only one person, sometimes there’s a huge team behind it. Depending on the project, this phase can be concluded in a very short time or take very long. Furthermore, this is done both in academia or in industry. Actually, there are quite a lot of tutorials out there, so with the adequate help also you would be able to train a small (not so complex) ML model and deploy it.

Some challenges of Machine Learning

AI applications can be found basically everywhere. They are of huge support and help to make life easier. AI-made decisions (or suggestions for decisions) can also have serious impacts on people’s lives.

Particularly, ML can become very complex and offer many sources of error. For example, errors can happen during data collection; imagine an incorrect or biased data collection or wrong data documentation. During data preparation, relevant factors can be filtered out incorrectly. During the training process, errors can occur in the actual programming and in the selection of parameters. When applying the previously trained model, it can happen that the new data of the application field does not fit to the previous situation. Finally, the results can of course also be misinterpreted.

On a societal level, a great danger is that the training data used for the training process is considered perfect. A perfect data set would require all possible factors that constitute or influence a situation to be recorded. This is actually never possible. Data is always only a simplified representation of the situation with a limited number of factors taken into account. This is especially the case when it comes to data on our societies.

Indeed, data that is supposed to represent our society will always include all problems and inequalities of our world, because they simply exist. These structures (or patterns) are learned by the learning ML algorithm and are then also reflected in the final prediction. This can lead to biased predictions to the disadvantage of those societal groups that are for instance less represented in the data set, even though the data set might depict a representative society.

Simply put: garbage in, garbage out.

For the case of bias in ML, this means that biased data will also result in biased predictions. And because, as mentioned above, ML’s core strength is finding patterns in data and deriving inferences, the used data has a critical role for ML. In fact, the quality of results from ML, highly depends on the quality and the amount of the data. For ML to provide good results, it is important that data sets are big enough. Usually, the size of data exceeds the amount of data that humans would be able to analyze properly. However, it is not always easy to either find already available good data sets or collect good data oneself. This is for example the case when it comes to rare phenomena, or societal contexts that are hard to quantify. When the data sets are either not good enough or simply too small, ML results can easily lack accuracy and be poor in quality. Interestingly, many advances in the fields of AI and ML can not be traced back to highly innovative algorithms, instead, it is because of the vast amount of available data that AI models provide promising predictions.

Who is responsible?

Similarly to AI, also ML is an umbrella term and comprises many different tools, for example deep learning. Depending on the applied tool, it is difficult to understand how a ML system reached a certain result, because the logic of the systems is sometimes hard to comprehend. This is a major issue: Who is responsible (accountable) for the results of AI use? If there is an accident? A wrong diagnostic? Or discrimination against someone?

Transparency can help ensure accountability, e.g. how did a ML-based health application come to a certain illness prediction or why did the self-driving car take a left and not a right turn?

Understanding how models come to their results is important to determine liability, especially in the case of wrong decisions or an accident.

However, many ML models such as deep learning algorithms are very complex and rather black boxes than anything close to transparent, making for example bias issues hard to solve. Therefore, if an application area requires a clear way to identify responsibility, then it might be good to choose a ML tool that has a less complicated logic, even though it potentially produces less accurate results. Besides the complexity of the model, transparency issues also arise with state or corporate secrecy. Many ML processes are secret and can not be monitored by the public.

Additionally, ML algorithms often are only trained to solve very specific tasks. Slight changes in the problem to be solved can come along with the need to retrain the algorithm for the new task. Sometimes, training an algorithm can take days, thereby consuming a lot of energy and having a high environmental impact. For the training of complex algorithms, a regular personal computer does not suffice, because a lot of computational power is needed.

Concluding, not all contexts, in particular not all social situations, provide good preconditions to apply AI solutions. Data is not neutral and not perfect. It mirrors, in a simplified and incomplete form, societal structures including biases and structural inequalities. The ML algorithm learns from these patterns and generates results based on these patterns. ML models are only as good as the training data on which they were trained on and as precise as the individuals designing, programming and applying the model take care of its proper development and application.

Towards rules for governing AI

Although the list of challenges described above is by far not complete, the mentioned issues already exemplify that some form of governance is necessary in order to avoid negative effects from the application of AI. Up until now, there have already been many discussions on national levels on how AI should be governed. Several countries released national AI strategies and likewise nearly all big companies and NGOs published papers on their perception of good AI practices.

Many of these documents contain indeed a lot of valuable ideas and proposals. While ethical aspects of AI have been widely elaborated on, the implementation of such principles is still a big question mark and for this reason in the center of attention of many institutions today. Furthermore, national discussions have taken place, but the Internet, as one of the main technologies enabling AI applications, makes AI a global thing. For this reason, a coherent approach as opposed to a patchwork of national approaches (including data or privacy laws) could ensure all communities to feel benefits from AI. That being said, AI governance is still at an early phase and discussions that include all stakeholders, including industry, governments and users, are highly needed.

We would like to present you one set of recommendations and discuss these with you. We picked the policy proposals by the Ad Hoc Expert Group (AHEG) to UNESCO that published their draft text of recommendations on the ethics of AI in mid May this year. The group formulated the following eleven policy proposals, which they assigned to five goals and which should be read as policy recommendations to the Member States. We chose this text because UNESCO is a UN organization with global coverage.

GOAL I: Ethical Stewardship

1. Promoting Diversity & Inclusiveness

Diversity and inclusiveness refers to the active participation of all Member States, to the disclosure and combat of cultural and social stereotypes and inequalities in the functioning of AI systems as well as their training data, to the possibility for users to report disparities, to the awareness and respect of local and international cultural differences and norms, to the closure of diversity gaps in the development of AI systems and to the spread of AI ethics into all relevant fora.

GOAL II: Impact Assessment

2. Addressing Labour Market Changes

In order to properly address changes in the labour market, Member States should provide adequate educational programs for all generations. This includes upskilling and reskilling measures, but also reconsidering educational programs in general. To forecast future trends, researchers should analyze the impact of AI on the local labour market. Corporations, NGOs and other stakeholders should strive to achieve a fair transition of employees most likely to be affected by changes in the labour market. Finally, policies should address especially underrepresented populations in order for everyone to take part in the digital AI-driven economy.

3. Addressing the social and economic impact of AI

To prevent inequalities, Member States should prevent any AI-relevant monopolies (e.g. research, technology, data, market). In cooperation with partners, AI literacy education should reduce digital access inequalities and digital divide. Furthermore, evaluation and monitoring mechanisms as well as AI ethics policies or AI system certification should be introduced. Member States should encourage private entities to launch impact assessment, auditing, monitoring and ethical compliance measures such as exchange with different stakeholders in the AI governance or the introduction of an AI Ethics Officer. Additionally, data governance strategies should ensure good quality of training data.

4. Impact on Culture and on the Environment

AI systems should be incorporated to preserve, enrich and understand cultural heritage. It should be examined and addressed how AI systems such as voice assistance or automated translation influence human language and researched what long-term effects result from interaction with AI systems. AI education for professionals from the creative professions as well as evaluation and awareness of AI tools to avoid concentration should be promoted. Furthermore, the environmental impact of AI systems should be assessed and reduced.

GOAL III: Capacity Building for AI Ethics

5. Promoting AI Ethics Education & Awareness

AI ethics should be embedded into curricula of schools and universities, whereby collaboration between technological and societal domains should be promoted. Additionally, ‘prerequisite skills’ for AI education should ensure the acquisition of coding skills, basic literacy and numeracy. General awareness programs of AI as well as access to knowledge on challenges and opportunities should be promoted. Moreover, it should be researched how AI can be used in teaching. People with disabilities, people from diverse races and cultures as well as women should especially be promoted to participate. Best practices should be monitored and shared with other Member States.

6. Promoting AI Ethics Research

Member States should invest in research in AI ethics or incentivise investments by the private sector. Training in research ethics of AI researchers and the inclusion of ethical considerations in the design of their research and the final product (including analysis, annotation and quality of datasets and scope of results) should be ensured. The scientific research community should be supported by both Member States and industry by facilitating the access to data. Also gender diversity in academic AI research and industry should be promoted.

GOAL IV: Development and International Cooperation

7. Promoting Ethical Use of AI in Development

The ethical use of AI should be encouraged by Member States. Together with international institutions, they should strive to provide platforms that allow for international cooperation on AI development (infrastructure, funding, data, domain knowledge, expertise, workshops). Furthermore, networks and research centers for international collaboration of AI research should be promoted.

8. Promoting International Cooperation on AI Ethics

Member States should conduct AI ethics research through research institutions and international organizations. All entities should ensure equal and fair application of data and algorithms. International cooperation should be encouraged to bridge geographical differences or particularities.

GOAL V: Governance for AI Ethics

9. Establishing Governance Mechanisms for AI Ethics

AI governance mechanisms should be inclusive (participation of diverse people of all age groups), transparent (oversight, fact-checks by media, external audits, reviews by fora), multidisciplinary (holistic examination of issues) and multilateral (international agreements). A digital ecosystem for ethical AI, that includes infrastructure, digital technologies and knowledge sharing options, should be developed and granted access to. Furthermore, AI guidelines with ethical considerations should be developed and used. Eventually, an international legal framework could be developed and implemented to foster international cooperation between countries and other stakeholders.

10. Ensuring Trustworthiness of AI Systems

Measures to monitor an AI system lifecycle (data, algorithms, actors) should be implemented by Member States and private entities. Moreover, clear requirements for transparency and explainability of AI systems should be set based on the application domain, the target audience and the feasibility. Therefore, research on explainability and transparency should especially be promoted by Member States through extra funding. Moreover, the development of international standards for levels of transparency should be considered in order to enable an objective assessment and the determination of compliance of systems.

11. Ensuring Responsibility, Accountability and Privacy

AI governance frameworks to achieve responsibility and accountability for content and outcomes throughout the entire AI system lifecycle should be reviewed and adapted. Higher goal is to ensure liability or accountability for AI-decisions, whereby only natural or legal persons must be liable and have responsibility over AI-decisions, not the AI systems themselves. Not existing norms should be established with actors from the entire AI ecosystem spectrum. Specific measures that accelerate the development of new policies and laws should be introduced. Harms caused by AI systems should be invested, redressed and punished. Furthermore, the fundamental right to privacy should be secured through appropriate measures and individuals should be able to take advantage of the concept “the right to be forgotten”, which includes the possibility of overseeing the usage of one’s own private data and the option to delete it. Personally identifiable data should be subject to high security. Finally, a Commons approach to data should be adopted. This would promote interoperability of the data sets and allow high standards in overseeing collection and utilization.

And you?

Looking forwards

Who should take care of the Internet?

What is “governance” and why it matters

Governance can be simply defined as a process of taking decisions. It has two components: Who is involved, and what is everyone’s role.

We therefore have to understand who is playing which role. Why is this important? Because the decisions that are taken have an impact on us all, and on future generations.

With the increased popularity of the Internet came a host of issues. There is no doubt that today’s Internet problems are complex and intertwined. For instance, in order to protect our consumer’s rights, there needs to be legislation which holds companies accountable for any breaches. Governments need to be careful that while protecting consumers, they are not stifling the efforts of companies to invest in new infrastructure and technology, as this drives development forward. Companies need to be able to make profits, but this should not come at the expense of our rights to privacy, or the safety of our personal data. If our data is stolen by criminals, law enforcement needs tools to be able to track down criminals in whichever country they are, and to bring them to justice, while respecting our privacy and the privacy of our communications.

Similarly, improving the security of the Internet requires tough laws, well-equipped law enforcement agencies, a stronger corporate culture of responsibility, and campaigns to educate users on how to protect themselves and behave responsibly online. If we only focus on one aspect, such as the legal part, we are missing out on other areas which are also part of the solution.

There is also a question of scale: Many players are willing to tackle the issues globally, knowing that global solutions help drive progress forward. This is not easy: while the government of a country decides on policies which apply nationally, regional and global policies require broad agreement. And on the contrary, many topics may be better solved at local level, with actors from the ground.

Internet Governance 101

Stakeholders use various tools to tackle, or govern, Internet issues, and to shape the future development of the Internet. They consult other players, enact rules, use enormous amounts of data to help them make sound decisions, and draw on experiences from other areas of everyday life which are governed in one way or another.

Since Internet issues are very complex, decisions are sometimes difficult to reach. Governments may be reluctant to consult other players, since they often feel they hold the main responsibility for governing the Internet. Companies sometimes use the investment argument to counter any attempts by governments to create new regulations. Civil society sometimes fails to understand that companies have a bottom line, that of making money. The technical community sometimes backs the companies’ arguments simply because many “techies” are employed by big companies. And academia’s proposals and suggestions are sometimes difficult to implement (though they may look great on paper).

Over the years, players created many solutions to help overcome these challenges. Solutions are often driven by values and ideals, such as the need to respect human rights, or the need to make the Internet and technology accessible to everyone. Some of these ideals can be found in documents, or conventions, agreed to by governments around the world. Others are developed by international organisations and civil society organisations, based on deep insights into what has worked and what has not. In brief, many frameworks, models, and mechanisms already exist to tackle the main problems. And remember also: players have their own needs and interests, which are often ‘under the bonnet’.