Stakeholders’ Dialogue on the Digital Cooperation Architecture

Balanced Information Briefing

These materials are the product of a process of collaborative co-production and iterative improvement, created for the “We the Internet Project”, proposed by Missions Publiques, written by Matthias C. Kettemann and the Missions Publiques team, under the supervision of the Scientific Committee and the Advisory Board of the project and at the initiative of the strategic partners (Germany’s Federal Foreign Office, UNESCO, Facebook, Google, Federal Office of Communication of the Swiss Confederation, World Wide Web Foundation, Wikimedia Foundation, World Economic Forum, European Commission, Internet Society).

They are licensed under a Creative Commons License, Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/).

Publication Director: Antoine Vergne (antoine.vergne@missionspubliques.com).

https://digitalcooperation.org/

Table of Contents

Summary

- In the past 40 years, the Internet has become a global phenomenon that affects all humanity, even those that are not connected.

- Hence the Governance of the Internet – simply defined as a process of taking decisions on the future of the Internet – has become a key question of our time.

- As a scientific project, the early days of the Internet were driven by an aspiration to communicate. One of the most notable differences between then and now, is that back in those days, many challenges were not evident and were not big problems. With the increased popularity of the Internet came a host of issues. Companies, the technical community, and academic institutions were the first to get together and discuss them. The voice of civil society grew stronger, and governments – who had funded the creation of the earlier projects – also joined the other actors to tackle these issues.

- The actors all came together during the so-called World Summit on the Information Society (between 2003 and 2005). During this meeting, the actors agreed to (a) to initiate a global forum, called the Internet Governance Forum, which meets every year to discuss pressing policy issues; (b) on a set of commitments, called the Tunis Agenda, which are reviewed every year.

- In 2018, the UN’s Secretary General asked a group of experts to suggest how to improve this whole landscape of solutions, action plans, mechanisms, and the rest. Players are now discussing these suggestions, which should help improve drastically how certain issues are tackled. The group was called the High-Level Panel on Digital Cooperation and published its report in June 2019.

- In this report, The UN is seen as an essential player in shaping the digital transformation, through international norms and through the evolution of cooperation architectures.

- The High-level Panel has recommended strengthening global digital cooperation mechanisms.

- Germany and the United Arab Emirates have been asked by the UN Secretary-General to act as champions for the development of recommendations building on various options for digital cooperation architectures from the Panel’s report.

- Missions Publiques organizes a global stakeholders´ dialogue on June 5th/6th whose ideas will be integrated into the champions’ options paper on the future architectures of digital cooperation.

- Recommendation 5A of the Panel contains three key recommendations by the High-level Panel: (1) that the UN Secretary-General facilitate an agile and open consultation process to develop updated mechanisms for global digital cooperation, (2) mark the UN’s 75th anniversary in 2020 with a “Global Commitment for Digital Cooperation”, and (3) “the designation of a UN Tech Envoy”.

- Recommendation 5B raises issues that can be framed under five headings, including the merging of multilateral and multi-stakeholder formats, the reliance on, and reform of, existing cooperation architectures, a holistic approach to Internet governance combining different national regulatory systems from data to consumer protection and competition law, and the necessity to stress-test new governance approaches before rolling them out globally.

- Digital cooperation is essential to securing the use and development of the Internet, which lies in the common interest.

- The Report identifies 14 principles, which future digital cooperation architectures should respect in order to ensure accountable and legitimate decision-making processes and thus increase output legitimacy.

- The Report also identifies 10 key functions that future digital cooperation architectures should be structurally ready to satisfy.

- Marking the UN’s 75th anniversary, a Global Commitment for Digital Cooperation should enshrine principles, functions and objectives of an improved global digital cooperation architecture.

- The Digital Commons Architecture seeks to develop governance solutions based on a commitment to safeguarding the Internet in the common interest through multilateral and multi-stakeholder tracks.

- The Distributed Co-Governance Architecture is based on horizontal networks of experts that quickly develop voluntary norms so convincingly that states and other actors see them as “normative solutions” to adopt and enforce.

- Building on existing structures, the Internet Governance Forum Plus adds functionalities to the world’s biggest global Internet-related multi-stakeholder forum (held under a UN mandate) to increase its legitimacy and effectiveness and remedy institutional shortcomings.

- We need to keep one overarching goal in mind when debating principles and discussing functions of global digital cooperation, when building institutions and reforming digital cooperation architectures: There is one world and one Internet and we need to reaffirm our common vision for its future, so we can be responsible stewards of the Internet – all stakeholders individually and all stakeholders together in light of the global common interest in securing the integrity of the Internet, its norms, order, institutions and cooperation architectures.

Background, Context and Motivation

Internet and Internet Governance are key to our future

In the past 40 years, the Internet has become a global phenomenon that affects all humanity, even those that are not connected.

Hence the Governance of the Internet – simply defined as a process of taking decisions on the future of the Internet – has become a key question of our time.

As a scientific project, the early days of the Internet were driven by an aspiration to communicate. One of the most notable differences between then and now, is that back in those days, many challenges were not evident and were not big problems. With the increased popularity of the Internet came a host of issues. Companies, the technical community, and academic institutions were the first to get together and discuss them. The voice of civil society grew stronger, and governments – who had funded the creation of the earlier projects – also joined the other actors to tackle these issues. The actors all came together during the so-called World Summit on the Information Society (between 2003 and 2005). During this meeting, the actors agreed to (a) to initiate a global forum, called the Internet Governance Forum, which meets every year to discuss pressing policy issues; (b) on a set of commitments, called the Tunis Agenda, which are reviewed every year.

There is no doubt that today’s Internet problems are complex and intertwined. For instance, in order to protect our consumer’s rights, there needs to be legislation which holds companies accountable for breaches within their responsibility. Governments need to be careful that while protecting consumers, they are not stifling the efforts of companies to invest in new infrastructure and technology, as this drives development forward. Companies need to be able to make profits, but this should not come at the expense of our rights to privacy, or the safety of our personal data. If our data is stolen by criminals, law enforcement needs tools to be able to track down criminals in whichever country they are, and to bring them to justice, while respecting our privacy and the privacy of our communications.

Similarly, improving the security of the Internet requires a mixture of different interventions: tough laws, well-equipped law enforcement agencies, a stronger corporate culture of responsibility, and campaigns to educate users on how to protect themselves and behave responsibly online. If we only focus on one aspect, such as the legal part, we are missing out on other areas which are also part of the solution.

There is also a question of scale: Many players are willing to tackle the issues globally, knowing that global solutions help drive progress forward. This is not easy: while the government of a country decides on policies which apply nationally, regional and global policies require broad agreement.

Stakeholders use various tools to tackle, or govern, Internet issues, and to shape the future development of the Internet. They consult other players, enact rules, use enormous amounts of data to help them make sound decisions, and draw on experiences from other areas of everyday life which are governed in one way or another.

Since Internet issues are very complex, decisions are sometimes difficult to reach. Governments may be reluctant to consult other players, since they often feel they hold the main responsibility for governing the Internet. Companies sometimes use the investment argument to counter attempts by governments to create new regulations. Civil society sometimes fails to understand that companies have a bottom line, that of making money. The technical community sometimes backs the companies’ arguments simply because many “techies” are employed by big companies. And academia’s proposals and suggestions are sometimes difficult to implement (though they may look great on paper).

Over the years, players created many solutions to help overcome these complex and intertwined challenges mentioned above. Solutions are often driven by values and ideals, such as the need to respect human rights, or the need to make the Internet and technology accessible to everyone. Some of these ideals can be found in documents, or conventions, agreed to by governments around the world. Others are developed by international organisations and civil society organisations, based on deep insights into what has worked and what has not. In brief, many frameworks, models, and mechanisms already exist to tackle the main problems. And remember also: players have their own needs and interests, which are often ‘under the bonnet’.

Yet, this is not enough. Mechanisms need to be updated or improved. Overlapping mechanisms need to be sorted out. This is why the UN’s Secretary General last year asked a group of experts to suggest how to improve this whole landscape of solutions, action plans, mechanisms, and the rest. Players are now discussing these suggestions, which should help improve drastically how certain issues are tackled.

The UN is a vital player in shaping the digital transformation, through the evolution of cooperation architectures

The United Nations is a key international player in the process of shaping digital transformation. At various points in time and through different organs and agencies, the UN acts

- as a convener for conferences and multi-stakeholder-based or multilateral initiatives on digital cooperation;

- by opening a space where norms and values are debated, such as at the Internet Governance Forum;

- as a standard-setter through e.g. the International Telecommunication Union’s Standardization Sector;

- as a space to develop the capacity of members, e.g. the Digital Blue Helmets initiative and the UN Office on Drugs and Crime’s Global Programme on Cybercrime;

- by ranking, measuring and mapping, e.g. the Global Cybersecurity Index;

- as a space for arbitration and dispute-resolution, e.g. the World Intellectual Property Organization’s Internet Domain Name Process.[1]

The scale, spread and speed of change brought about by digital technology is unprecedented, but the current means and levels of international cooperation are unequal to the challenge. From business to politics and personal relationships, digital transformation fuels so many aspects of our lives. Digital transformation is crucial in building a more sustainable world and needs better cooperation across domains and borders to realising the full social and economic potential of digital technologies. As a global community, we face questions about security, equity, sustainability and human rights in a digital age.

The High-level Panel has recommended options to improve global digital cooperation

While the United Nations and its special organizations produce a vast array of reports each year, only a select few signal a turning point in global governance. One of these was the 2019 report The Age of Digital Interdependence by the UN Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel on Digital Cooperation.[1] After a comprehensive multi-stakeholder consultation process lasting nine months, the panel, chaired by Jack Ma and Melinda Gates, published five sets of recommendations to strengthen international cooperation with the goal of “ensuring a safe and inclusive digital future for all, taking into account the relevant human rights standards”:

- build an inclusive digital economy and society;

- develop human and institutional capacity;

- protect human rights and human agency;

- promote digital trust, security and stability;

- foster global digital cooperation.[2]

In this consultation process, we focus on the fifth set of recommendations, on developing updated multi-lateral and multi-stakeholder mechanisms for global digital cooperation that are, inter alia, adaptive, inclusive and fit for the purpose. Specifically, in Recommendations 5 A and 5 B of the Report[3] the High-level Panel urgently recommends that the UN Secretary-General facilitates processes to update “global digital cooperation” mechanisms, pass a “Global Commitment for Digital Cooperation” on the occasion of the UN’s 75th anniversary in 2020 to enshrine the values underlying an improved global digital cooperation architecture and to appoint a Technology Envoy (5A). The High-level Panel also recommends an adaptive and agile, inclusive and purpose-suitable “multi-stakeholder ’systems’ approach for cooperation“.[4]

In the run-up to the publication of the Report, over 100 organizations provided feedback. In order to collect feedback, develop options and amplify progress, key UN member states and organizations were entrusted with the task to be “champions” for each recommendation. The governments of Germany and the United Arab Emirates, together with the office of the Special Adviser to the UN Secretary-General, were named champions for Recommendations 5A/B on the Digital Cooperation Architecture.[5]

Germany and the United Arab Emirates champion the development of ideas to further discussion and consideration on Panel’s recommendations on more digital cooperation

As co-champions, Germany and the United Arab Emirates together coordinate consultations with other states, companies, civil society actors, academics, community representatives and technical experts. Their important and ambitious goal is to find ways to implement the ideas proposed by the High-level Panel with relation to the digital cooperation architecture. To make sure that the process of substantiating the ideas of the Report leads to the best possible results, the co-champions are taking care to consult widely, ensure diversity and regional and gender balance among the stakeholder involved and identify common values and principles.

The goal of the two governments is to identify ways to implement the ideas of the High-level Panel that are endorsed by the widest possible ‘coalition’ of stakeholders. These will then be formulated as concrete options for the UN and other Internet policy-makers to take in an “Options Paper”, which Germany will deliver to the UN Secretary-General in summer 2020.[1]

Missions Publiques organizes a global Dialogue on the Future of Internet, which includes a dialogue with stakeholders whose ideas will be integrated into the champions’ report on the future architectures of digital cooperation

Missions Publiques (MP) is an organization ensuring that the voices of citizens are heard with regard to issues ranging from participatory municipals budgeting processes to updating global Internet governance regimes. On 5 and 6 June 2020, Missions Publiques is holding a Global Stakeholders’ Dialogue to allow input by stakeholders into the process of answering the key questions of Internet governance.

Ideas, perspectives and solutions brought by stakeholders will substantiate Recommendations 5A/B of the Report. The present materials give background to this process and can be used to inform and inspire discussions.

Recommendations 5A and 5B of the High-Level Panel Report

Recommendation 5A: We recommend that, as a matter of urgency, the UN Secretary-General facilitate an agile and open consultation process to develop updated mechanisms for global digital cooperation, with the options discussed in Chapter 4 as a starting point. We suggest an initial goal of marking the UN’s 75th anniversary in 2020 with a “Global Commitment for Digital Cooperation” to enshrine shared values, principles, understandings and objectives for an improved global digital cooperation architecture. As part of this process, we understand that the UN Secretary-General may appoint a Technology Envoy. [1]

Recommendation 5A contains three key proposals by the High-level Panel: (1) a Global Commitment for Digital Cooperation, (2) an updated global digital cooperation architecture, and (3) the designation of a UN Tech Envoy.

(1) The Global Commitment for Digital Cooperation (GCDC)[1] should be developed in a multi-stakeholder-based, accessible process and have an impact on par with the Sustainable Development Goals. The GCDC should substantiate the key functions of digital cooperation and confirm its principles, such as consensus-orientation, subsidiarity, accessibility, inclusiveness, agility, accountability, resilience, technological neutrality – and commit to maximizing public interest internationally and being anchored in public benefit nationally.[2]

(2) The Report also recommends several options to improve global digital cooperation. Such an architecture should uphold and reinforce common values, Cooperation should be “inclusive; respectful; human-centred; conducive to human flourishing; transparent; collaborative; accessible; sustainable and harmonious.“ Architectures should be based on operational principles which are responsive to the key criticism of the status quo the Panel identified:[3] they should “be easy to engage in, open and transparent; inclusive and accountable to all stakeholders; consult and debate as locally as possible; encourage innovation of both technologies and better mechanisms for cooperating; and, seek to maximise the global public interest.“[4] The Panel asked the UN Secretary-General to kickstart a process to define criteria for a successful reform of cooperation architectures with – importantly – the options discussed in Chapter 4 of the Report as a starting point. The three options are: extending and strengthening the Internet Governance Forum (“IGF+“), using a Distributed Co-Governance Architecture (COGOV) or a Digital Commons Architecture (DCA) coordinated by the UN.[5]

(3) The Report also recommended the appointment of a UN Tech Envoy to proactively identify concerns to be solved by the updated architectures, to offer coordination for multi-stakeholder initiatives, to promote norms related to the Internet, to advise the UN Secretary-General, to ensure the mainstreaming of Internet issues into UN policies and agencies and to support the build-up and maintenance of “international digital common resources“.

Recommendation 5B: We support a multi-stakeholder “systems” approach for cooperation and regulation that is adaptive, agile, inclusive and fit for purpose for the fast-changing digital age.[1]

Recommendation 5B, though short, raises issues that can be framed under five headings:

(1) Digital cooperation and regulation (or, rather, as is more often used with regard to the Internet, ’governance’) will require reinvigorated multilateral partnerships and new multi-stakeholder-based mechanisms: While the circumstances and the regulatory goals will greatly influence how digital cooperation is realized, both multilateral (state – state) and multi-stakeholder (state – civil society – private sector – academia – technical sector) approaches will be useful.

(2) There is no need to reinvent the wheel: The Panel recommends improving the existing normative mechanisms, rather than creating new ones. However, when existing forums and formats have proven ineffective, it may be necessary to develop new approaches.[1]

(3) There is no need to glorify binding norms and wait with the introduction of necessary governance mechanisms until international legal rules crystallize or even a treaty is passed. Rather, soft governance approaches based on multi-stakeholder participation can develop a fact-based, participative process of deliberation and design, including governments, private sector, civil society, users and policy-makers, and lead to formally non-binding but nevertheless persuasive and legitimate norms.

(4) The High-level Panel supports the “systems“ approach, which foresees the primacy of the regulatory goal over the normative architecture (function follows form): Combining different national legal sub-orders, such as competition law, data protection law and consumer law (and their national oversight bodies), allows for agile processes in which trade-offs are fairly considered.[2]

(5) Digital cooperation approaches need to be stress-tested: Any new governance approach in digital cooperation should also, wherever possible, look for ways – such as pilot zones, regulatory sandboxes or trial periods – to test efficacy and develop necessary procedures and technology before being more widely implemented.

Digital cooperation is essential in securing human rights online and offline.

The importance of the Internet’s integrity – its security, stability, robustness, resilience and functionality – has been widely accepted. It is also broadly recognized that the purposes and principles of the UN Charter should guide Internet-related rulemaking. The 2015 report of the UN Group of Governmental Experts confirmed that international law, including the UN Charter and international legal principles, applies fully to the Internet.[1] Indeed, the international community aspires to regulate the Internet in a peaceful manner “for the common good of mankind”.[2] While the goal of international digital cooperation is thus clear, international law offers little clarity as to which principles and functions digital cooperation architectures should respect.

This is important because the order of Internet governance (or the normative order of the Internet[3]), like every social order, is related to a “specific understanding of the purpose, the goals and rules of this order.”[4] These functions need to be justified. The orders are thus “orders of justification” and the justifications are often formulated as narratives which then give sense and meaning to the order.[5] These orders thereby become meaningful and exert attraction through power of identification,[6] which in turn favors norm adherence. It is therefore important to understand what principles and functions the Panel identifies for digital cooperation architectures.

The Report identifies 14 principles, which future digital cooperation architectures should respect in order to ensure accountable and legitimate decision-making processes and thus increase output legitimacy.

An Annex to the Report contains a list of principles of digital cooperation.[1] These relate to the processes and outcomes of digital cooperation.

- Consensus-oriented: Decisions should be made in ways that seek consensus among public, private and civic stakeholders.

- Polycentric: Decision-making should be highly distributed and loosely yet efficiently coordinated across specialized centres.

- Customized: There is generally no “one size fits all” solution; different communities can implement norms in their own way, according to circumstances.

- Subsidiarity: Decisions should be made as locally as possible, closest to where the issues and problems are.

- Accessible: It should be as easy as possible to engage in digital cooperation mechanisms and policy discussions.

- Inclusive: Decisions should be inclusive and democratic, representing diverse interests and accountable to all stakeholders.

- Agile: Digital cooperation should be dynamic, iterative and responsive to fast-emerging policy issues.

- Clarity in roles and responsibility: Clear roles and shared language should reduce confusion and support common understanding about the responsibilities of actors involved in digital cooperation (governments, private sector, civil society, international organizations and academia).

- Accountable: There should be measurable outcomes, accountability and means of redress.

- Resilient: Power distribution should be balanced across sectors, without centralized top-down control.

- Open: Processes should be transparent, with minimum barriers to entry.

- Innovative: It should always be possible to innovate new ways of cooperating, in a bottom-up way, which is also the best way to include diverse perspectives.

- Tech-neutral: Decisions should not lock in specific technologies but allow for innovation of better and context-appropriate alternatives.

- Equitable outcomes: Digital cooperation should maximize the global public interest (internationally) and be anchored in the broad public benefit (nationally).

The Report also identifies 10 key functions that future digital cooperation architectures should be structurally ready to satisfy.

- Leadership: generating political will among leaders from government, business, and society, and providing an authoritative response to digital policy challenges.

- Deliberation: providing a platform for regular, comprehensive and impactful deliberations on digital issues with the active and effective participation of all affected stakeholders.

- Ensuring inclusivity: ensuring active and meaningful participation of all stakeholders, for example by linking with existing and future bottom-up networks and initiatives.

- Evidence and data: monitoring developments and identifying trends to inform decisions, including by analyzing existing data sources.

- Norms and policy making: building consensus among diverse stakeholders, respecting the roles of states and international organizations in enacting and enforcing laws.

- Implementation: following up on policy discussions and agreements.

- Coordination: creating shared understanding and purpose across bodies in different policy areas and at different levels (local, national, regional, global), ensuring synchronization of efforts, interoperability and policy coherence, and the possibility of voluntary coordination between interested stakeholder groups.

- Partnerships: catalyzing partnerships around specific issues by providing opportunities to network and collaborate.

- Support and capacity development: strengthening capacity development, monitoring digital developments, identifying trends, informing policy actors and the public of emerging risks and opportunities, and providing data for evidence-based decision making – allowing traditionally marginalized persons or other less- resourced stakeholders to actively participate in the system.

- Conflict resolution and crisis management: developing the skills, knowledge and tools to prevent and resolve disputes and connect stakeholders with assistance in a crisis.

Marking the UN’s 75th anniversary, a Global Commitment for Digital Cooperation should enshrine principles, functions and objectives of an improved global digital cooperation architecture.

The Report suggests using the UN’s 75th anniversary, to be celebrated in autumn 2020, as the occasion to adopt, in the General Assembly, a “Global Commitment for Digital Cooperation” to enshrine shared values, principles, understandings and objectives for an improved global digital cooperation architecture. In one of the most successful global multi-stakeholder-based processes of developing Internet-related principles of the past the NETMundial Principles process, concluding in the adoption of the NETmundial Multistakeholder Statement (2014), Internet governance process principles figured prominently, while the functions and objectives were given less space. This time around, the GCDC should include both process-related and substance-related principles and be formulated with a view to defining the functions of global digital cooperation. The following questions should be considered:

- Is the multi-stakeholder-based “World We Want” process, which helped formulate the Sustainable Development Goals, suitable for the GCDC?

- Does it make sense to seek to adopt a new commitment when international law already enshrines key goals of global digital cooperation and states disagree on norms for responsible state behavior in cyberspace?

- The High-level Panel calls for consultations in each state and region for “ideas to bubble up from the bottom”: What insights or ideas anchored in a state or regional perspective can you share?

- How can we ensure that equitable participation and inclusiveness are already part of the process of agreeing on the principles (which should then include inclusiveness and equitable participation)?

- How does the GCDC align with (or build upon) other normative incentives of recent years, such as the Paris Call, the Singapore Norms Package, Microsoft’s cybernorms – and how to ensure that both the process of negotiating the principles and the principles themselves are characterized by greater coherence?

Digital Cooperation Architectures

The Report proposed three models for better digital cooperation as starting points for further discussion: a Digital Commons Architecture (DC), a Distributed Co-Governance Architecture (COGOV) and a reformed Internet Governance Forum (IGF+).[1] After a brief description of the idea behind the model, this report will identify the model’s potentials (which opportunities can be realized when the model is implemented), its spoilers (what can stop it from being successful) and then describe avenues of implementation (which can form the basis for policy discussions among stakeholders).[2]

The importance of the Internet’s integrity – its security, stability, robustness, resilience and functionality – has been widely accepted. It is also broadly recognized that the purposes and principles of the UN Charter should guide Internet-related rulemaking. The 2015 report of the UN Group of Governmental Experts confirmed that international law, including the UN Charter and international legal principles, applies fully to the Internet.[1] Indeed, the international community aspires to regulate the Internet in a peaceful manner “for the common good of mankind”.[2] While the goal of international digital cooperation is thus clear, international law offers little clarity as to which principles and functions digital cooperation architectures should respect.

This is important because the order of Internet governance (or the normative order of the Internet[3]), like every social order, is related to a “specific understanding of the purpose, the goals and rules of this order.”[4] These functions need to be justified. The orders are thus “orders of justification” and the justifications are often formulated as narratives which then give sense and meaning to the order.[5] These orders thereby become meaningful and exert attraction through power of identification,[6] which in turn favors norm adherence. It is therefore important to understand what principles and functions the Panel identifies for digital cooperation architectures.

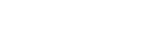

The Digital Commons Architecture

The Digital Commons Architecture seeks to develop governance solutions based on a commitment to safeguarding the Internet in the common interest through multilateral and multi-stakeholder tracks.[1]

- Ensuring the integrity of the Internet and the safety, security and stability of both its technical infrastructure and its standards and protocols is essential to a sustainable digitalization.

- Safeguarding the Internet (and safeguarding societies from negative consequences of the use and development of the Internet) is therefore in the global common interest (much like clean seas and the fight against climate change).

- Different tracks, with different stakeholder constellations, would establish a dialogue around current and emerging issues.

- Yearly meetings would substantiate insights from the tracks and develop commons governance iteratively and progressively, by developing soft law or more binding norms.

- “Commons” is a well-regarded concept that conceptually connects the Internet governance to the digital sustainability and sustainable digitalization discourse and makes obvious the importance of both technology (as commons) and governance (of the commons).

- Combining multilateral and multi-stakeholder tracks ensures that both normative approaches that safeguard the Internet in the common interest – international law and internet governance – are united.

- A yearly common meeting on the DCA focuses the attention on safeguarding the internet in the common interest. This could eliminate overlap due to the current multiplicity of forums. As each track can be headed by a different organization, monopolization of responsibility is not a worry.

- Aggregating lessons from the different tracks into soft law or more binding approaches will lead to bottom-up iterative learnings on governance.

- A repository of norms and governance practices to guide stakeholders in their respective roles and responsibilities can have very positive normative effects.

- As the UN provides only light coordination, the energies might diffuse and some tracks might be more active than others.

- The concept of “commons” itself is difficult to map directly onto the Internet with its many layers, players and points of control. The regimes applicable to aspects of the Internet are more intricate than, say, the law of seabed mining.

- As the DCA does not specify technical solutions, but only models, the implementation may be difficult.

- The Report points to voluntary contributions or membership fees as a financial basis. This may increase the recurring problem of underrepresentation of marginalized stakeholders.

- Like existing Internet governance formats, no enforcement mechanisms are envisaged. Stakeholders that do not subscribe to the commons model can only be ‘punished’ by decentralized sanctions.

- The concept of what “commons” is with regard to the Internet, its layers, stakeholders and points of control needs to be clarified. What “commons” are there to be governed? What is the added value of referring to “digital commons”?

- How does international law protect digital commons, especially in light of global commitment to the Sustainable Development Goals?

- Commons research has a long history. What past examples of successful technology commons exist? What can we learn from them and what failures/tragedies should be avoided?

- In any commons regime, the less powerful are disadvantaged because there is no central authority ensuring equitable treatment. How can the DCA solve this dilemma? And how can the DCA solve the challenge that many communication spaces are ruled by private actors?

- In common regimes outliers might profit from self-serving behavior. Therefore some sort of enforcement mechanism will need to be developed to ensure that the commons are not misused.

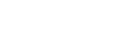

The Distributed Co-Governance Architecture

The Distributed Co-Governance Architecture is based on horizontal networks of experts that quickly develop voluntary norms so convincingly that states and other actors see them as “normative solutions” to adopt and enforce.[1]

- The Distributed Co-Governance Architecture relies on self-forming ‘horizontal’ networks of experts, who create norms in the tradition of the Internet Engineering Task Force and the World Wide Web Consortium.

- The goals of the networks is to rapidly produce shared digital cooperation solutions, including norms, and provide them to stakeholders.

- Stakeholders, including states, can consider these “voluntary” normative solutions and adopt them. Norm implementation and norm enforcement would therefore be separated from the norm design phase.

- In order to ensure coherence over time and across topics the HLPDC foresees three organizational entities: Digital Cooperation Networks (issue-specific horizontal collaboration groups), Network Support Platforms (to host and enable the dynamic formation and functioning of multiple digital cooperation networks), and Network of Networks (to coordinate and support activities across all digital cooperation networks and network support platforms).

- An annual forum, a ‘research cooperative’ and a ‘norm exchange’ should further contribute to coherence across policies and normative instruments.

- Differentiating between norm design, norm implementation and norm enforcement allows developing issue-based multi-stakeholder Digital Cooperation Networks that can develop norms without any implementation or enforcement pressure built into the process. States (and other stakeholders) can then freely choose to adopt these and provide the norms with enforcement mechanisms under national laws.

- When multi-stakeholder networks act as norm entrepreneurs, better norms can be developed. Better norms are usually more easily accepted, which leads to processes of norm diffusion and norm cascades.

- When companies who set norms for private communication spaces contribute to norm design processes together with states, the emerging norms can be more easily squared with both private regulatory interests and public values.

- Creating norms is visible and a visibly successful process, which would reduce critique of digital cooperation architectures as being “talking shops”.

- Horizontal self-organizing networks of norm creators are similar to issue-specific adhoc governance groups of the past, who have successfully come together to fight certain computer viruses, so there is a COGOV track record.

- Open, horizontal multi-stakeholder models are in danger of stakeholder capture, especially by actors strategically pursuing self-interests.

- Many norms will not be so ‘successful’ as to cascade towards compliance. Intrinsically motivated norm adherence or norm application by states is a wide bet.

- The whole process is, as any global governance process, premised upon presence, network-building and epistemic power and might therefore reinforce pre-existing biases and discriminatory practices.

- Political science tells us how difficult it is to develop replicable models of norm entrepreneurship. Only really successful ones are progressively implemented until a tipping point is reached, after which norms start to cascade (and are applied broadly) and, in a final step, are decentrally internalized through prohibitive (reputational, economic …) costs for non-compliance.

- Without a strong coordination, the exercises in norm entrepreneurship might rather be reflective of current powerful stakeholder positions in the process and not of the truly sensitive regulatory demands.

- How can we ensure that the right issues are normatively prioritized by the horizontal networks? There must be some way to control for selection bias.

- At which point would a coordinating institution, which should probably be stronger than a network of networks, make sense to ensure integrity and enable coherent outcomes?

- Since it is mostly governments that are responsible for implementing norms and providing them with an enforcement architecture, how can a special role in the process be ensured for them without losing the multi-stakeholder character of the process?

- Apart from including states, the most important precondition of a legitimate norm is the legitimacy of the process in which it emerged. Following Jürgen Habermas, any COGOV model must develop a functional democratic discourse model that ensures equitable and inclusive participation. Can we learn from the last decades of Request for Comments approach to norm-building through community-based rough consensus?

The Internet Governance Forum Plus

Building on existing structures, the Internet Governance Forum Plus[1] adds functionalities to the world’s biggest Internet-related multi-stakeholder forum with a UN mandate to increase its legitimacy and effectiveness and remedy institutional shortcomings.

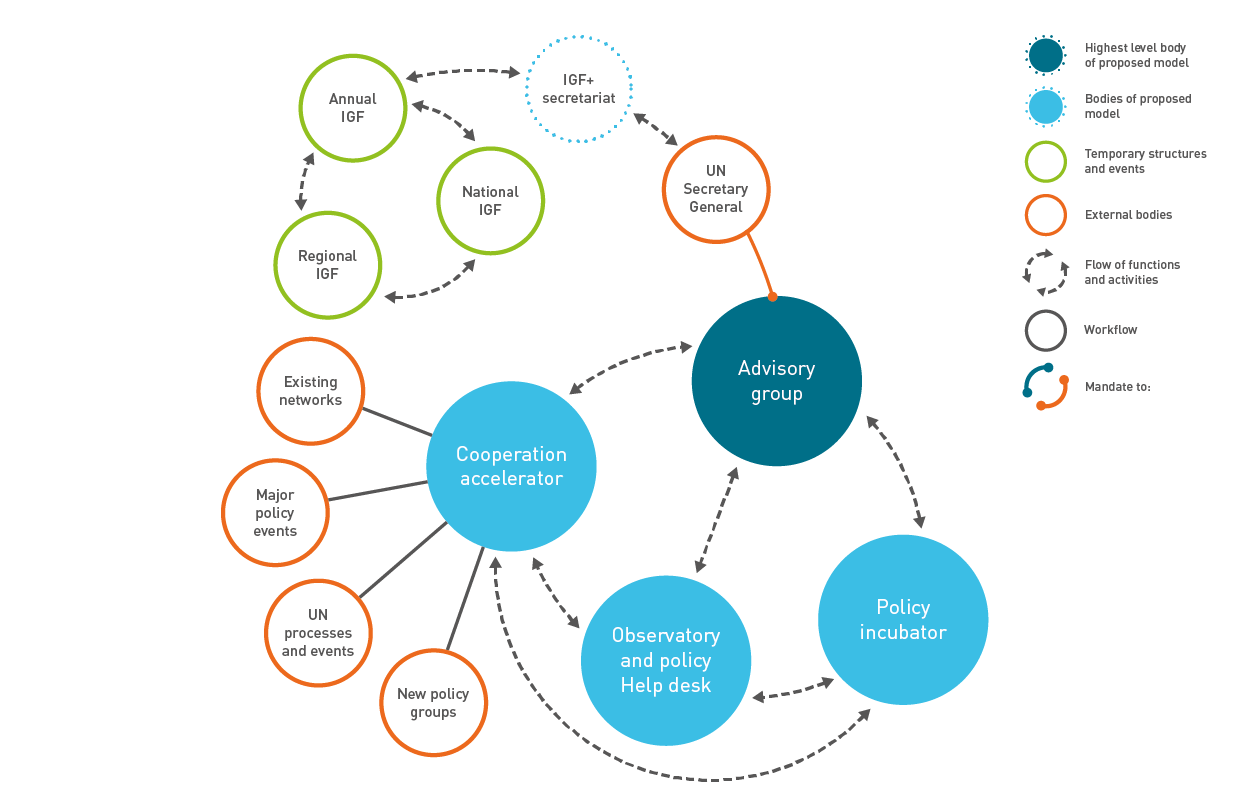

- The IGF+ model builds on the existing Internet Governance Forum, which has had a UN mandate since 2005 as the main space for all stakeholders to address Internet governance issues and add multi-stakeholder and multilateral legitimacy by increasing inclusive representativity, enhancing normative outputs and stabilizing the IGF’s institutional anchor within the UN systems. Five new instruments serve these goals.

- The Advisory Group (based on the current Multi-Stakeholder Advisory Group) would be responsible for preparing meetings, identifying focus policy issues and aiming for more coherence of discussions on the governance spectrum. Members are appointed by the UN Secretary-General for three years.

- The Cooperation Accelerator should accelerate cooperation across governance institutions and processes and ensure coherence between debates in different Internet governance settings. It should consist of members with multidisciplinary experience and expertise and include ambassadors of key digital events to ensure that non-UN policy tracks are taken into account as well.

- The Policy Incubator would seek out regulatory gaps and then build coalitions to proposed norms and policies to fill them. As the missing link between dialogue platforms like the IGF, which identify gaps and decision-making bodies that might not have the necessary Internet policy expertise, the Incubator can suggest non-binding norms.

- The Observatory and Help Desk helps coordinate requests to draft legislation, to tackle crisis situations or to provide advice on policy, and to coordinate capacity- and confidence building activities.

- The IGF+ Trust Fund is a dedicated fund for the IGF+ with contributions from all stakeholders.

- The IGF+ model builds on the existing IGF, including its Dynamic Coalitions and Best Practice Forums, 114 national and regional IGFs, and its strong commitment to gender and regional balance. The acquis of the IGF is a strong foundation.

- Two key areas in which improvement is considered necessary are the lack of actionable outcomes (“talking shop”) and the limited participation of governments and businesses (“civil society-led”). The five new institutions seek to provide answers especially to these two aspects.

- The Cooperation Accelerator as an informal mechanism of enhanced coordination and communication bridges gaps between discussion infrastructures and decision-making architectures. In particular, the CA would allow for regulatory innovations to be widely distributed.

- As over the years Dynamic Coalitions (DCs) and „Best Practice Forums“ (BPFs) have emerged within the IGF process to organize intersessional work and provide normative outputs, a Policy Incubator could build on their successes and link their work.

- One of the IGF’s functions could be to dispatch issues to relevant organisations and stakeholder groups.Its main outcome doesn’t need to necessarily be norms, it can simply facilitate cooperation. State representatives will most likely not engage so openly when norms are at stake.

- None of the five envisaged new IGF+ bodies comprehensively addresses inequalities in access and inequitable participation.

- The IGF’s geographical focus on Western Europe for the last meetings is left unaddressed.

- Institutions such as the observatory should not duplicate existing structures (it might make more sense to conceive of them as a meta-observatory, observing existing norm collections, case databases and best practice forums).

- More bodies and institutions usually lead to more fragmentation and more siloed debates. Does the model not run the risk of watering down the IGF’s unique position?

- What do stakeholders actually expect from the IGF? Do they want it to change substantially? How can it move from being an event to being a process? Can existing Dynamic Coalitions and Best Practice Forums and National and Regional Initiatives (NRIs) be developed into Incubators with the support of the Observatory? Or would they lose their unique vision and expertise?

- How can we ensure that the Internet Governance Forum, which remains the most successful and respected communication space for Internet governance, moves from being seen as a “talking shop” to becoming a “doing shop”, namely where concrete initiatives take shape and start from? Or would this fundamentally change the atmosphere with participants then mired in long discussions about semantics in new rules and not on the larger issues at hand?

- Do the five suggested bodies – Cooperation Accelerator, Policy Incubator, Observatory and Help Desk, IGF+ Trust Fund – sound promising? Are they responsive to the faults of the IGF?

- Should the MAG be strengthened to maintain its strategic role for developing the programme of the IGF’s annual meeting?

- Are the IGF+ bodies enough to ensure that all topical issues can be quickly dealt with: from ad hoc coalitions to fight specific viruses to the development of norms for responsible state behavior?

- Would it make sense to provide the IGF with a recommendation power as envisaged by the Tunis Agenda?

- Discussing secretariats might sound boring, but do they have a central role in ensuring continuity in work and coherence? How can the IGF Secretariat be supported – perhaps by more closely linking it to the UN Office in Geneva?

Next Generation Internet Governance

We need to keep one overarching goal in mind when debating principles and discussing functions of global digital cooperation, when building institutions and reforming digital cooperation architectures: There is one world and one Internet and we need to reaffirm our common vision for its future, so we can be responsible stewards of the Internet – all stakeholders individually, and all stakeholders together in light of the global common interest in securing the integrity of the Internet, its norms, order, institutions and cooperation architectures.

Inclusivity is key to developing legitimate international governance approaches. All future models of digital cooperation architectures need to be designed in a way that ensures representativity – i.e. meaningful and “equitable participation of developing countries, women and other traditionally marginalized groups who have often been denied a voice.”[1] Both architectures and the normative results they reach are only legitimate when the decisions they make are based on truly inclusive processes that take account of all stakeholders. Decisions about rights and interests of people should be taken in a way that can be explained to them. We have the right to justify the decisions that impact us – in national, regional and global settings. Therefore we have to ask how to best ensure representativity and equitable participation of those who have been denied a voice in the past.[2]

As representativity usually starts as close to ‘home’ as possible, improving digital governance at the national level should be front and center of national political agendas. This can then feed into international governance improvements, such as the ones presented and discussed in this paper.

The key questions we will have to ask ourselves in preparing submissions on the co-champion’s report on future digital cooperation architectures are

- which principles and functions should be key to digital cooperation reform and how should they be agreed upon;

- how we can ensure coherence with norm-development activities in other forums, such as the two working groups under the auspices of the UN General Assembly;

- how we can ensure inclusivity and equitable representation; and

- how we can usefully combine elements of different architectures to complement the IGF+ model.

All three architectures – COGOV, DCA, IGF+ – are based on a fluid approach to normativity on the Internet. This allows us to distinguish between norm-creation processes and the emergence (or reform) of normative bodies, such as the IGF+. Participation by all relevant actors proceduralizes legitimacy and symbolically validates the norms, independent of the norms’ epistemic legitimacy. The inclusion of all relevant actors in normative processes is not only the closest approximation to an ideal discourse but also the procedural translation of democratic legitimacy in transnational constellations.

The themes of the Panel report are central to the reform of the digital cooperation architectures, namely:

- a new generation of cooperation models, combining multi-stakeholderism and multilateralism;

- financial independence of cooperation-oriented institutions by the installation of a dedicated trust funds to enhance inclusivity;

- a reduction of policy inflation by consolidating discussions across forums; and

- a light coordination and convening role for the UN

Further, the Report rightly highlighted that digital cooperation and governance will require reinvigorated multilateral partnerships and new multi-stakeholder-based mechanisms, that it will usually make more sense to use existing normative mechanisms, rather than create new ones; that soft governance approaches based on multi-stakeholder participation can lead to formally non-binding but nevertheless persuasive and legitimate norms; that the function of cooperation must dictate how the cooperation architecture is conceived; and that any digital cooperation approach needs to be stress-tested before being widely used, ideally in smaller (regional) governance settings.

This Stakeholder Dialogue takes place at a key time in the discussion process of how states and other stakeholders should cooperate in developing norms on the use of digital technology and the mitigation of risks stemming from their use. The insights gathered today in meetings like this all across the world will flow into the co-champions’ draft options paper, which will be circulated to key constituents by the end of June 2020. By July 2020, feedback will be implemented and by August 2020 the two co-champions will submit the Options Paper to the UN Secretary-General.

This dynamic is important, as 2020 is only the first year of a decade where the future of Internet governance will be debated in the run-up to 2025, when the WSIS+20 process will allow us to reflect on the goals of the Outcome Documents of that summit and whether we have realized the potential of the Internet. Recall that at the end of the two-phased World Summit on Information Society (WSIS) states affirmed in the Tunis Commitment their goal to build a “people-centred, inclusive and development-oriented Information Society” premised on the “purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations, international law and multilateralism, and respecting fully and upholding the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.”[3] In “international as in national affairs” relating to Internet governance, states “resolve[d] to strengthen respect for the rule of law.”[4]

While the High-level Panel was active at digitalcooperation.org, Germany’s website as co-champion is at global-cooperation.digital. This is no accident. The many months of stakeholder discussions culminating in the 5th and 6th June Global Stakeholders’ Dialogue and Stakeholder Dialogue across the world have substantiated not only the ideas by the panel, but have also highlighted that the key governance questions of the future are not only about digital cooperation, but about new principles and procedures for global cooperation – this time applied to the digital realm and the future of Internet Governance but with much potential to manage and safeguard, use and develop other rights and interests in the global common interest.

While building institutions and reforming cooperation architectures we should not forget that architectures do not exist for themselves. They are means to an end, namely to achieve the goals of Internet governance, as expressed in the Tunis Commitment (though they also contribute to confidence-building and therefore are also an end in themselves). International society’s goals regarding Internet governance can only be achieved when the digital cooperation infrastructures are used to further substantive Internet governance politics in key areas. These include at least four “baskets”[5]:

(1) Human security: Stakeholders may start discussions on a Digital Peace Plan, including norms for good behaviour of states and non-state actors in cyberspace and confidence-building measures to counter (neo)nationalist policies that endanger the stability and functionality of the global Internet and its infrastructure, encompassing human rights-based approaches to national security (including military aspects and confidence-building measures), the fight against cybercrime and technical security and network resilience;

(2) Human development through and with sustainable online economies: Stakeholders should adopt a Digital Sustainability Agenda to promote human rights-sensitive (digital) economies based on market-driven innovation with data flowing freely in trusted environments, in which sustainable economic growth and decent work are ensured, where the next billion Internet users are brought online; and, generally, to drive forward the realization of the UN Sustainable Development Goals;

(3) Human rights: Stakeholders may commit to a Digital Human Rights Agenda, providing norms and policies to respect, protect and implement human rights on the Internet, based on existing norms, targeted at all relevant stakeholders, in their respective roles;

The institutions we are building, the digital cooperation architectures we are reforming, the norms of responsible state behavior in cyberspace we are developing all need to keep this overarching goal in mind. We need to be responsible stewards of the Internet – all stakeholders together. According to the motto of the 2019 IGF in Berlin: There is one world and one Internet and we need to reaffirm our common vision for its future, so we can be responsible stewards of the Internet – all stakeholders individually, and all stakeholders together in light of the global common interest in securing the integrity of the Internet, its norms, order, institutions and cooperation architectures.